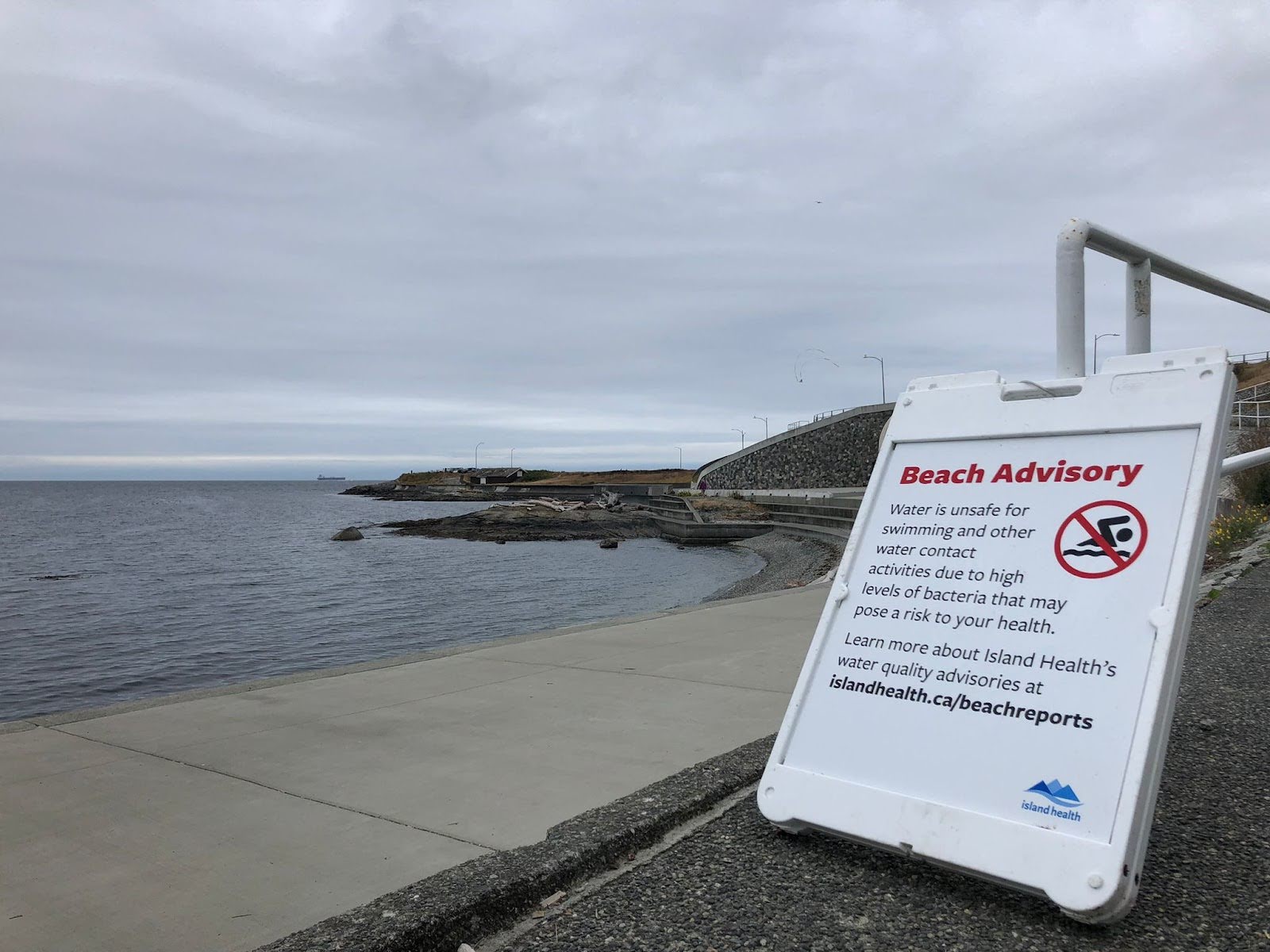

About once a week, I drive my dog to Swengwhung (Clover Point) – a small peninsula on the southern tip of Vancouver Island – for a walk along the water. Recently, this has been something of a surreal experience. In spite of signs warning that the water is unsafe for contact due to high levels of bacteria, if the sun is shining, then there are people out having a swim, windsurfing, or paddleboarding.

An image of a Sea Wolf, by Butch Dick, decorates an exhaust stack at Swengwhung (Clover Point). The peninsula was once a point of defence for Lekwungen Peoples, who still harvest plants such as Camas in the area. But the Sea Wolf also sits on top of the Clover Point Pump Station: a facility that provides “bypass pumping” to an outfall off-shore when intense rainfall or snowmelt (i.e., stormwater) gets into the sewer system and overwhelms the city’s pipes. In areas with combined sewer and stormwater systems (like Čeqʷəŋín ʔéʔləŋ / Oak Bay and Vancouver), heavy rains can overload pipes even more easily than when these systems are separate.

The City of Victoria started pumping raw sewage into the ocean at Swengwhung way back in 1892. As part of the Capital Regional District or “CRD,” it was infamous as the “last major coastal community in North America” to finally stop this practice. It took an overwhelming amount of public pressure, and intervention from both BC and the federal government, before the CRD built a sewage treatment plant.

Yet high levels of E.coli and enterococci bacteria – signs of fecal contamination – are still showing up in the waters around Greater Victoria. And people keep swimming in it. Island Health has been vague about the sources, saying only that “[e]levated bacteria levels may be due to a variety of factors, including water temperatures, tides, or stormwater…”

A beach advisory warning people that water is unsafe for swimming and other water contact at Ross Bay Beach. The Clover Point Pump Station is in the background.

Thinking about all this got me wondering: how do you get people talking about something as decidedly unsexy as sewage treatment or, the main focus of this blog, the out-of-sight, out-of-mind issue of polluted stormwater?

In Part One of this two-part blog series, we explored sewage and stormwater in urban settings; how stormwater polluted with chemicals like 6PPD-quinone from tires is affecting urban creeks and fish; and how stormwater still exists in a kind of regulatory no-man’s land. Now, we’ll talk about how to address these regulatory and practical gaps.

How can we stop stormwater from harming fish?

Green stormwater infrastructure: Benefits for natural flows and water quality

With supportive provincial policies, local champions have done much good work over the past decade or so to re-think urban drainage and develop ‘green infrastructure’ (“GI”). Green infrastructure helps the landscape absorb rainwater, instead of relying on pipes and drains (‘grey infrastructure’) to carry it rapidly away. Features like rain gardens, urban tree canopies, “bioswales” (imagine those strips of grasses, flowers, or shrubs you sometimes see between the road and sidewalk), and even thicker layers of topsoil all can play a role here, especially if they are used in a strategic way across sites, neighbourhoods and watersheds.

More green infrastructure means less demand on aging grey infrastructure (which is expensive to replace, much less expand). This is particularly important with more frequent extreme weather events. It also means improved stream health: green infrastructure reduces erosion of streambanks during periods of heavy rainfall (less water surging out of pipes into creeks), and helps maintain a steady flow of water underground that finds its way to streams and creeks during dry periods.

Not only does green infrastructure help manage flows, we are also learning more and more about how it benefits water quality by filtering out harmful contaminants from roads and other urban surfaces, and also cooling water temperatures.

And there’s more: the Public Health Agency of Canada has even published a report connecting green spaces – including green infrastructure – to both a reduction in chronic diseases and increased community resilience in the face of climate change.

In the Lower Mainland, scientists at the University of British Columbia are collaborating with local governments like Vancouver and Surrey to figure out where to create GI so that it can have the greatest impact on reducing pollutants. And on Vancouver Island, the British Columbia Conservation Foundation has teamed up with scientists at Vancouver Island University to create the interactive Tire Wear Toxins database, which shows levels of 6PPD in waterways from Campbell River to Victoria, in the hopes that governments will take action in priority watersheds.

One of the biggest barriers for local governments when it comes to GI is – you guessed it – funding. The term ‘infrastructure deficit’ is well known to local governments, and describes the gap between the resources needed to expand, replace and upgrade municipal infrastructure, and the resources available to do so. Recognizing this, water infrastructure experts have identified strategies for how to develop green infrastructure cost-effectively, including by integrating GI with planned infrastructure improvements and incentivizing businesses and property owners to install GI on private property.

Squelching my way into a rain garden to take a few quick pictures. It had been a hot summer week, and my garden at home was in need of watering, but the soil in the rain garden was still nice and wet.

The City of Victoria is one of a small number of municipalities in Canada with an incentive program already in place. In 2016, the City started charging property owners a fee based on how much their property relies on the municipal stormwater system for drainage services (the more of your property is covered in hard surfaces where water can’t sink to the ground, the more you pay). Through the City’s Rainwater Rewards Program, some property owners can apply for rebates to install GI, while others who have installed GI can apply for up to 50% off their annual stormwater fee. Funds from stormwater fees are used to finance upgrades to the City’s stormwater system.

Other local governments in Canada with stormwater fees and programs similar to Victoria’s include Newmarket, Halifax, and Kitchener. After intense rain and floods earlier this year, the City of Toronto is also considering whether to impose stormwater fees specific to commercial properties with lots of hard surfaces, like parking lots.

Improving regulation and oversight

Incentive programs are only one piece of the puzzle. As discussed in the first blog, local governments in BC have the opportunity to develop ‘Liquid Waste Management Plans’ (LWMP) that include stormwater plans, or alternatively to develop stand-alone stormwater management plans. But these plans are not required by law (although the Minister of Environment and Climate Change Strategy may direct a local government to develop an LWMP). Nor do local governments have to systematically and strategically consider watershed health when they are making infrastructure and land use decisions, even if they do have stormwater plans. In practice, this means that decisions about where and how to invest in green infrastructure are not necessarily leading to improvements to watershed health, as shown by the 6PPD-q examples.

For ideas about how to regulate stormwater more systematically, we might look to the south. Since the late 1980s, stormwater in the US has been regulated by the federal Clean Water Act (CWA). If a public entity in an urban area (like a medium or large city, and many small municipalities) owns a stormwater system that is separate from its sewer system, then it must apply to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) or a state permitting program for a permit to release stormwater into US waters. Municipalities with these systems must also create a detailed stormwater management program.

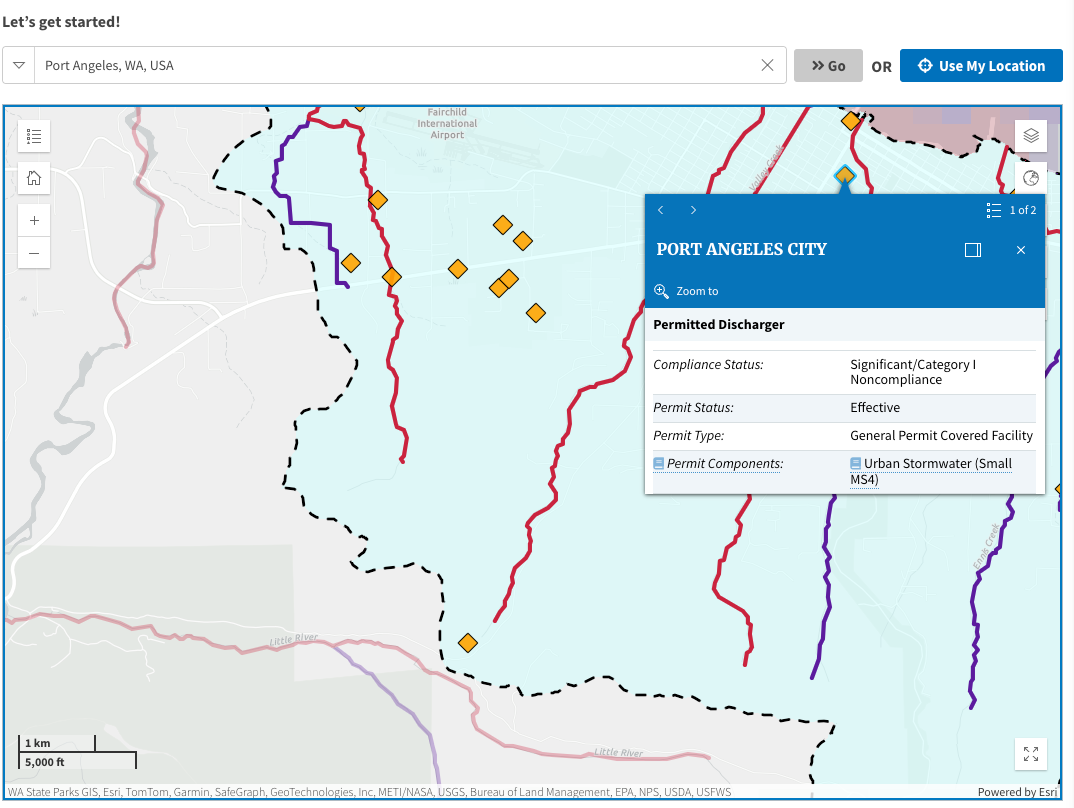

The EPA inspects municipal stormwater systems for compliance with the CWA, and does audits of stormwater management programs. Municipalities with combined systems that collect both stormwater and sewage also have to get a permit and meet federal water quality standards. The EPA even has a website where residents can quickly search up the status of their municipality’s permits:

For fun, I searched up Port Angeles, which is across the water from my home in Victoria. As of August 13 2024 – the How’s My Waterway? public database says that Port Angeles City is noncompliant with its MS4 (“municipal separate storm sewer system”) permit.

While US commentators contend that the Clean Water Act needs more teeth to deal with certain types of waterway pollution, including agricultural run-off, it does create accountability for municipal stormwater that is discharged through municipal drains.

What does this change, in practice? State governments have delegated authority to implement the permitting requirements for stormwater management, and the Washington Department of Ecology has an extensive program that involves municipal permitting, reporting, oversight, resources and education. When researchers discovered that 6PPD-quinone in urban road run-off was having a deadly effect on coho as they returned to streams to spawn, the state legislature allocated $528,000:

…solely for the department to work with the department of transportation, University of Washington-Tacoma, and Washington State University-Puyallup to identify priority areas affected by 6PPD or other related chemicals toxic to aquatic life from roads and transportation infrastructure and on best management practices for reducing toxicity.

…

[The Dept. of] Ecology recognizes that our salmon bearing watersheds and streams have Treaty Rights and reserved rights attached to them by federally recognized tribes. This sets a high priority for Ecology and other state agencies to quickly determine and implement remedial efforts on 6PPD-q in consultation with Indian Tribes.

This work was completed on an interim basis in October 2022, and the Department of Ecology has both published best practices to manage and reduce the impacts of 6PPD-q, and increased funding to its stormwater capacity program for local governments. The Department is also leading and supporting research to better understand the environmental impacts related to 6PPD-q.

In BC, by contrast, the Province has developed draft water quality guidelines for 6PPD-q, but it isn’t clear how it will apply them to stormwater discharges, which it doesn’t currently regulate. Federally, after a formal application from environmental groups, the Minister of Environment and Climate Change agreed to assess the chemical for possible listing as a toxic substance under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act. Scientists at Fisheries and Oceans Canada are apparently monitoring 40 creeks around the south coast to determine ‘hotspots’ and will eventually offer information to local governments that can be used to mitigate the pollution. There is no indication to date of a regulatory response relying on the Fisheries Act provisions to protect fish and fish habitat.

Public advocacy

In order for governments to seriously consider taking on something like more systematic regulation of stormwater at the watershed level, they usually need to know that it matters to the public. And here is where I start thinking, again, about all those people swimming at Swengwhung.

Personally, in spite of considering myself an environmentalist for a long time, I didn’t start thinking deeply about sewage or stormwater until working at West Coast. For the majority of my life in Victoria – from the time I was a kid into my early twenties – I was more or less unconscious of the fact that everything I flushed down the toilet was going straight into the ocean. And until earlier this year, I’d never even heard of the toxic tire chemical 6PPD-q.

In an interview with the Tyee about E.coli at False Creek in Vancouver, underwater photographer Fernando Lessa said that “[w]hen we collectively label places as dirty we turn our backs on them and this takes pressure off politicians to fix sewage and pollution issues.” For Lessa, “[t]he threat for nature is not garbage or sewage, since those can be fixed. The real danger is ignorance.”

Maybe the push for governments to take action on stormwater needs a mascot like Mr. Floatie, the “cheeky mascot known for protesting Victoria’s decades-long practice of dumping raw sewage” into the ocean. What this mascot might be, I’m not sure. Maybe a baby coho salmon.

If we’re going to transform stormwater policy and practices, then we need to go further with green infrastructure and take a strategic, systemic approach that prioritizes benefits for community and watershed health; we need law reform for stronger regulations at the provincial and federal level; and we need public education and advocacy, so that communities feel empowered to look after local streams and fish. But we also need to change the ways that we think about our responsibility to the water and other living beings.

When asked why SELEK-TEL (Goldstream River, a well-known spawning ground for coho and chum salmon in W̱SÁNEĆ territory) is so important, Tsartlip First Nation Elder ZȺWIZUT Carl Olsen told writer Denise Nadeau:

…we have a responsibility to look after this place that has provided for us for thousands of years, both in the way of salmon and the environment itself with foods and plants and medicines. It is really important that we start looking after the environment in a good way, in a way that is meaningful and protects those who can’t protect themselves – the fish, the salmon, the birds.

Many communities have local streamkeeper groups and other volunteer-led organizations focused on healthy watersheds. If you’re interested in getting more engaged with keeping your local watershed safe from polluted stormwater, consider checking out some of these local initiatives.

On Vancouver Island:

- Friends of Bowker Creek Society

- Letter writing campaign by James Bay United Church

- Peninsula Streams & Shorelines

In the Lower Mainland:

When Rain Becomes Dangerous (a two-part series)

- Part 1: Who is responsible for the impacts of polluted stormwater?

- Part 2: How can we stop stormwater from harming fish?

Top photo: a rain garden in sxʷeŋ'xʷəŋ taŋ'exw (James Bay, Victoria) / All photos provided by Kai Fig Taddei