I’m pleased to announce the release of a major new report – Payback Time? – What the internationalization of climate litigation could mean for Canadian oil and gas companies.

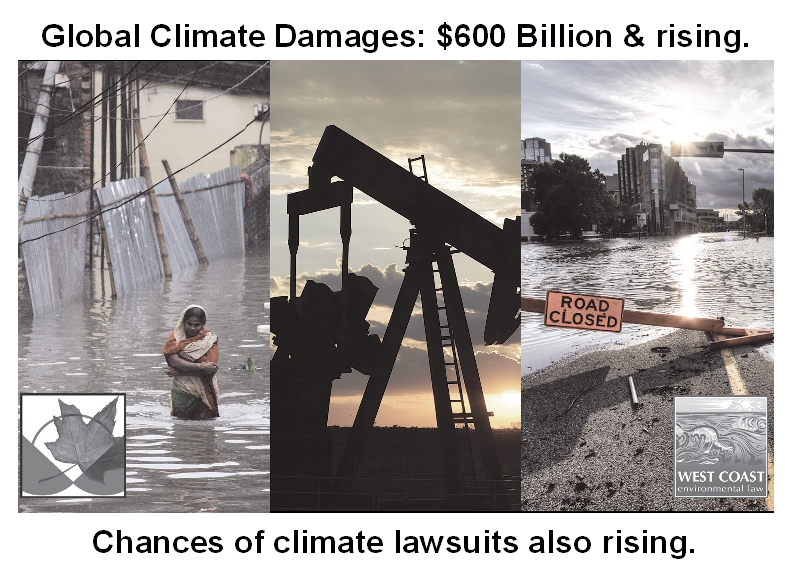

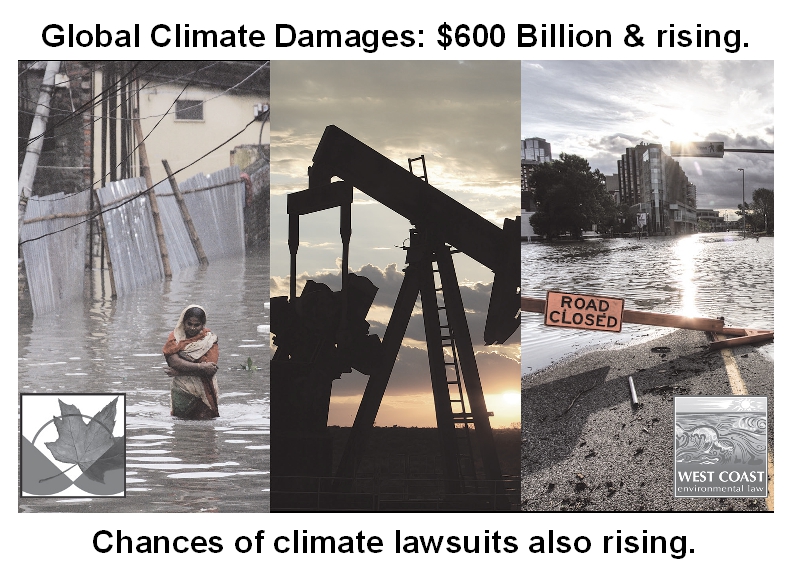

I’ve been writing about some of the themes in this report for some time – that a growing conversation about climate damages, and who will pay for them, could translate into liability for large-scale Greenhouse Gas producers. But Payback Time emphasizes that this is not just a conversation that is happening in Canada, and that the real risk to Canadian companies may not be under Canadian law, but from lawsuits originating outside Canada.

Others have written about the potential for climate damages litigation here in Canada. Calgary lawyer, James Early, recently made the point that improvements in science and increasing damages mean that such litigation will occur in Canada:

Others have written about the potential for climate damages litigation here in Canada. Calgary lawyer, James Early, recently made the point that improvements in science and increasing damages mean that such litigation will occur in Canada:

Closer to home, the floods that ravaged Calgary and Southern Alberta in June 2013, caused at least $1.7 billion (yes, that’s $1,700,000,000.00) in damage and losses making it the most costly Canadian natural disaster on record. … It can surely be only a matter of time before a significant legal challenge is brought in Canadian courts on the issue of climate change. One could argue that there are 1.7 billion reasons to explore that possibility in the coming months.

I’m with Early on this – I think that you can’t have billions of dollars worth of damage, and increasingly reliable scientific evidence linking that damage to the product of a relatively small number of fossil fuel companies, and not expect some pretty major litigation.

But it turns out that what happens in Canada is only part of the picture. Climate change is international, and there is good reason to believe that someone who suffers climate damages in, say, Bangladesh, could bring a lawsuit against Canadian, U.S. and European companies in the Bangladeshi courts. As Michael and I write in an opinion piece appearing in today’s Globe and Mail:

It is becoming increasingly likely that companies could be sued by victims of climate change overseas, in countries with quite different legal systems. There, they might face lawsuits based on constitutional rights to a healthy environment, strict liability for environmental harm, or any number of other legal principles that don’t currently exist in Canadian law.

Once a foreign court has ordered a Canadian company to pay for climate damages, that order is a debt – which Canadian courts can be asked to enforce. Chevron is currently fighting court actions in Canada, the United States and Brazil that seek to enforce a $9.5-billion award handed down by the supreme court of Ecuador – for pollution caused by oil spills.

So the question facing the “Carbon Majors” – 90 entities whose operations and products have caused 63% of climate change – is not what does Canadian law say about their legal responsibility for climate damages, but what do the laws of Bangladesh, Philippines, Brazil, India, and, indeed, the law of any country where climate damages are occurring, say.

That’s important, because while judges in Canada and the U.S. may feel that a precedent-setting decision that imposes significant costs on international fossil fuel companies is very political, it’s not at all clear that a judge in a country that benefited less from the fossil fuel economy would feel the same way. And there’s always the possibility that one or more of those countries might pass laws making it easier to sue for climate change damages (just as BC passed laws making it easier for it to sue tobacco companies).

Would Canadian courts enforce a climate damages award from, say, Brazil? We believe that the odds are good that they would. But if Canadian courts decide not to, those same companies also have assets in the U.S., Europe, and elsewhere, and the courts there might enforce against them.

The result is a major risk that every Carbon Major should take note of. That includes 5 Canadian companies that are listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange – Encana, Suncor, Canadian Natural Resources, Talisman, and Husky – and whose operations and products we calculate are collectively responsible for an estimated $2.4 Billion worth of global climate-related damage per year.

And even if such judgments cannot ultimately be enforced, a foreign damages award, and the fight to enforce it, would lend faces to the presently faceless victims of climate change. It would begin to chip away at the social license of the fossil fuel companies, in the same way that tobacco litigation played a role in turning public opinion against cigarette companies.

I do not want to be taken as suggesting that litigation is the only or even the preferred way of addressing the losses suffered by the victims of climate disasters. But so long as governments and industry resist international agreements that would deal with compensation and reign in our global appetite for fossil fuels, climate victims will have to look to the courts.

The best way for fossil fuel companies and their shareholders to guard against the emergence of transnational lawsuits is to transition away from fossil fuel products, and to support international negotiations that will address issues of loss and damages in a more systematic way.

By Andrew Gage, Staff Lawyer