As anyone who has worked in environmental or social justice knows, sometimes change takes a very, very long time, somewhat like a glacier carving out a valley. Little, incremental changes take place that you don’t notice at the time, but that add up to earth-shattering differences in the long run. Sometimes, though, you can point to milestones, markers in time that help you distinguish when things took a turn.

As anyone who has worked in environmental or social justice knows, sometimes change takes a very, very long time, somewhat like a glacier carving out a valley. Little, incremental changes take place that you don’t notice at the time, but that add up to earth-shattering differences in the long run. Sometimes, though, you can point to milestones, markers in time that help you distinguish when things took a turn.

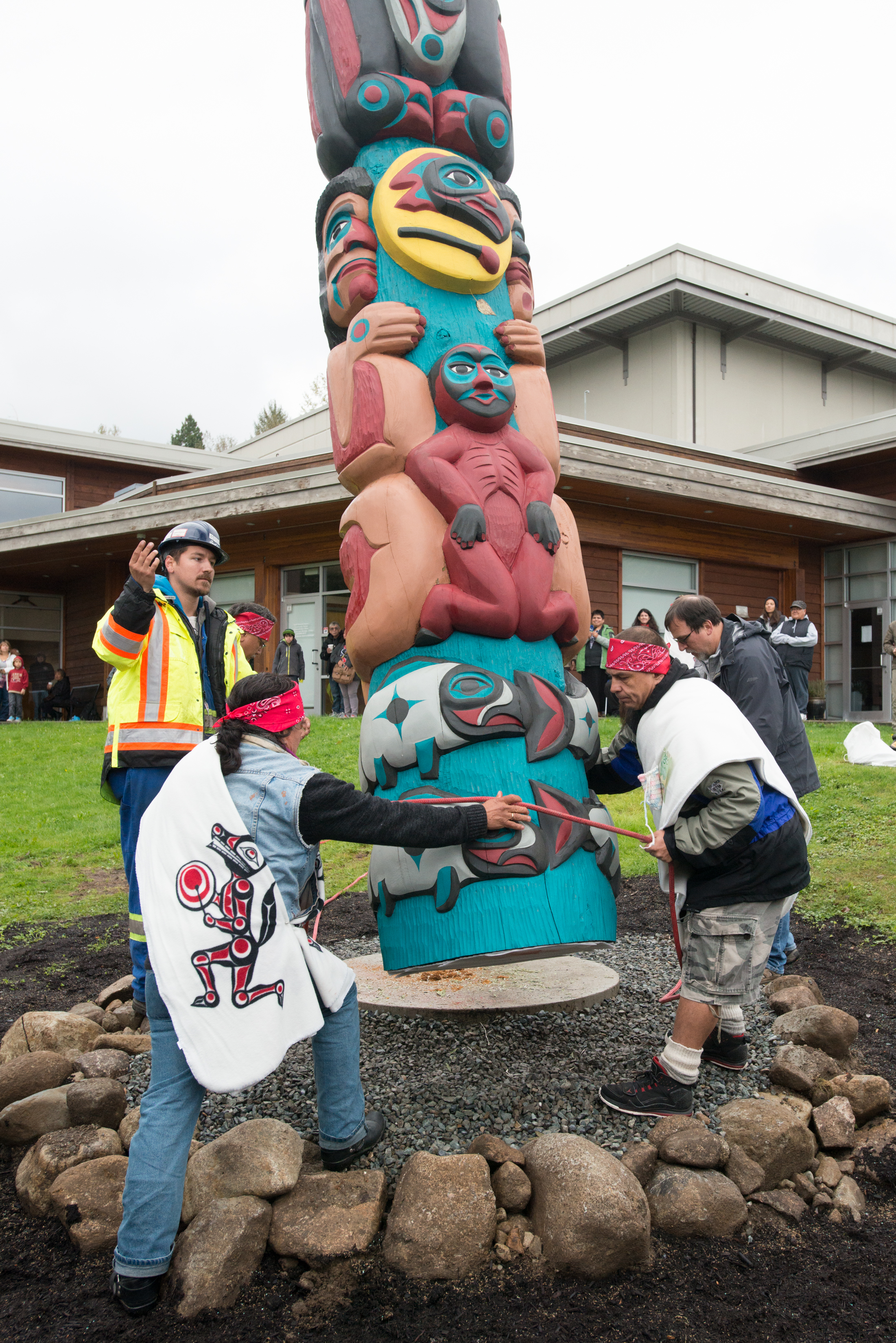

One of these moments occurred on September 29, 2013, when a unique totem pole was unveiled in Tsleil-Waututh territory. A gift from master carver Jewell James from the Lummi Tribe, the totem pole is intended as a permanent symbol of solidarity among Coast Salish Nations opposing destructive fossil fuel projects like Kinder Morgan's proposed pipeline and tanker expansion project. From its place in Tsleil-Waututh territory, the totem pole looks out across the Burrard Inlet to the Westridge Terminal, a symbol of awareness of the threats associated with the drastic expansion of tar sands oil tanker traffic proposed by Kinder Morgan for these waters. The totem pole has been given the name Kwel hoy’, meaning “we draw the line,” in the traditional language of the Lummi people. It stands as a powerful symbol of Tsleil-Waututh’s resolve to enforce their laws banning the expansion of tar sands infrastructure in their territory.

Staff from West Coast Environmental Law were honoured to be in attendance at the totem pole ceremony, to show our support and hear the stories from Tsleil-Waututh leaders, community members and witnesses speaking from the heart about why they are saying no to this project. They have myriad reasons for rejecting another pipeline, drawn from their long-term experience with living on and managing the land and water in their territory. According to the Sacred Trust Initiative:

Tsleil-Waututh, the people of the Inlet, have always relied on the bounty of the local waters and shores, which historically supplied us with a secure source of food. We have said ‘no’ to a new pipeline because of our experience with the old pipeline and the degradation of the Inlet. The existing pipeline has had four major leaks since Kinder Morgan took over pipeline operations in 2005 and two leaks in the past six months. The 2007 rupture of the pipeline in a Burnaby neighborhood spilled almost 250,000 litres (1500 barrels) of crude oil; enough flowed into Burrard Inlet to mark the shore on the other side. A spill in Burrard Inlet or the Salish Sea could result in more than $10 billion in economic costs alone and could never be fully cleaned up or remediated. The environmental effects of such a catastrophe would be irreversible.

For those who are unaware, since 1953, the Trans Mountain Pipeline has transported oil to the West Coast for local use. Kinder Morgan, the American oil company that purchased the pipeline in 2005, wants to dramatically expand the pipeline and tanker traffic in Burrard Inlet in order to sell tar sands oil to Asian and other international markets, ramping up the capacity of the Westridge Terminal oil port in Burnaby. This will mean a massive increase in tanker traffic in Burrard Inlet, and an increased risk of oil spills on the shores of the densely populated Lower Mainland. Neither First Nations nor the citizens of the Lower Mainland have ever been consulted about whether we want oil tankers here in the first place, and now industry wants to transform Vancouver into the world’s largest tar sands marine port.

Currently, the Trans Mountain Pipeline transports up to 300,000 barrels per day of tar sands oil. Kinder Morgan wants to build a new pipeline that will run alongside the existing pipeline, and will increase capacity to 890,000 barrels per day. Right now, approximately five oil tankers a month travel through the Burrard Inlet – if the expansion happens, oil tanker traffic will increase in the inlet to approximately one tanker per day.

Last year, the Tsleil-Waututh, Squamish, and Musqueam Nations, whose territories include Burrard Inlet and Howe Sound, signed the Save the Fraser Declaration, banning the transportation of tar sands oil through their territories – including the Lower Mainland – as a matter of Indigenous law. In addition, earlier this year, Tsleil-Waututh and Lummi Nations joined other Coast Salish nations in signing the International Treaty to Protect the Sacred from Tar Sands Projects. The Treaty commits tribal signatories to "mutual, collective, and lawful enforcement of our responsibilities to protect our lands, waters, and air by all means necessary." Now, the Coast Salish opposition to pipelines and tankers is symbolized not only by formal ratification of legal documents, but by a tall and steady sentinel. Kinder Morgan and our governments would be wise to take notice of Kwel hoy’ and the message that is now physically manifest on Tsleil-Waututh lands. Both promise to be here long after crude oil tankers have come, and gone from the Salish Sea.

By Jeanette Ageson, Communications and Development Manager