West Coast Environmental Law Association, along with a great many other Canadians, is disappointed that Bill C-38, the Budget Implementation Act, with its various attacks on Canada’s environment and the laws that protect it, has passed the House of Commons. With the Bill before the Senate, Members of Parliament (MPs) have gone home from Ottawa,  where they will doubtless receive a warm welcome from their constituents, as well as questions about the Budget and why significant changes to so many of Canada’s environmental laws were buried in it.

where they will doubtless receive a warm welcome from their constituents, as well as questions about the Budget and why significant changes to so many of Canada’s environmental laws were buried in it.

Here are our top questions that we’d like to suggest you ask your MP on their return home. You can find your MP’s contact information here.

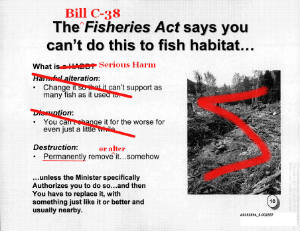

1. Why does Bill C-38 amend the Fisheries Act to reduce protection for the habitat of all fish – even for those that are part of the commercial, recreational and aboriginal fisheries that the government claims are still protected?

If your MP tries to tell you that Bill C-38 doesn’t weaken fisheries protection for all fish, point him or her to the sections of the Bill that make it illegal to cause “serious harm” to fish:

35. (1) No person shall carry on any work, undertaking or activity that results in serious harm to fish that are part of a commercial, recreational or Aboriginal fishery, or to fish that support such a fishery.

That might sound okay, until you realise that the current version of section 35 of the Fisheries Act which prevents all  harmful alteration of fish habitat, while “serious harm” is defined as only preventing actual death of fish or permanent alteration of their habitat. Under the “serious harm” provision, mining or logging activities could reduce the quality of fish habitat for years, so as to stunt the growth of fish or reduce the number of fish that can live there, as long as the alteration can’t be shown (beyond a reasonable doubt) to actually kill fish, and the fish habitat will eventually recover.

harmful alteration of fish habitat, while “serious harm” is defined as only preventing actual death of fish or permanent alteration of their habitat. Under the “serious harm” provision, mining or logging activities could reduce the quality of fish habitat for years, so as to stunt the growth of fish or reduce the number of fish that can live there, as long as the alteration can’t be shown (beyond a reasonable doubt) to actually kill fish, and the fish habitat will eventually recover.

The good news is that the “serious harm” provisions don’t become law, even after the Senate passes Bill C-38, until Cabinet says that they do, so you can still ask MPs what they will do to protect fish habitat and to stop this weakening of Canada’s Fisheries Act.

2. The government says that it’s not rewriting environmental laws for the benefit of the oil and gas industry, but many amendments are designed specifically to give special treatment to that industry, and especially oil and gas pipeline construction. Why do these amendments regulate the oil and gas industry less stringently than every other commercial enterprise in the country?

In addition to amendments to the Fisheries Act and a new Canadian Environmental Assessment Act 2012 that were on the wish list of the oil and gas industry, there are at least 5 areas in which Bill C-38 amends environmental laws to give the oil and gas industry special treatment; these relaxed rules don’t apply to any other industry in the country. The amendments:

- Eliminate the possibility that future environmental assessments for pipelines will be conducted by “review panels” – panels of experts that are arms length from government.

- Limit public participation in environmental assessment of energy pipeline projects to individuals who can demonstrate that they are either “directly affected” by the project, or have particular expertise or information that, in the opinion of the NEB, is relevant. This test, taken narrowly, has the potential to exclude a lot of people who live near or are otherwise indirectly affected by pipeline projects.

- Turn energy-related environmental assessments over to the National Energy Board (NEB) – an agency whose mandate includes, as a prominent feature, promoting the industry and which lacks specialized environmental assessment experience.

- Allow the NEB to sign off on pipeline projects without ensuring that the project’s impacts on the critical habitat of endangered species are minimized. All other federal government agencies that make decisions impacting endangered species habitat, and the NEB when considering non-pipeline related projects, are still required to minimize impacts on critical habitat.

- Take powers away from Transport Canada– which has a mandate and expertise related to navigation on public water bodies – related to the protection of public travel on waters, and gives it to the NEB, which doesn’t.

3. How many projects in Canada that would have received an environmental assessment under the old Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, will no longer receive an environmental assessment of any kind (federal or provincial) under the new Canadian Environmental Assessment Act 2012 (CEAA 2012)? Why are there no clear national standards for projects that will only be assessed at the provincial level? Doesn't the federal government have a responsibility to ensure high environmental standards are being applied nationally and in a consistent manner across the country?

CEAA 2012 will, among other things:

- significantly lower the number of projects that will be assessed for their environmental, social and economic impacts. While the government says that this is being done to avoid duplication, there will be many significant projects that no longer receive any environmental assessment, and the government has refused to say how many assessments will actually be done under the new Act;

- limit the “environmental effects” that must be evaluated, including eliminating assessment of how environmental changes may impact on non-Aboriginal human health and socio-economic conditions in most circumstances;

- offload responsibility for environmental assessment without ensuring that there is a consistently high national standard for environmental assessment that must be met. The result in many cases will be weak environmental assessments.

See our Report Card on the new CEAA 2012 and the Top 10 Concerns with Bill C-38 that we copublished with Ecojustice for a full list of the concerns about these and other changes.

4. Why does the new CEAA 2012 not contain any guarantees or definitions that will ensure that members of the public with a direct interest in a project or who are representing public interest concerns will be included in public participation?

The new CEAA 2012 will limit public participation for projects of national concern and pipeline projects to people who are “directly affected” or who have special expertise related to the project. In Alberta courts have previously ruled that “directly affected” excludes even members of the public in the communities closest to a project, hunters who hunt in the  area and others who do have a clear interest in the project.

area and others who do have a clear interest in the project.

New, strict timelines for all kinds of EAs will mean that there will necessarily be less time for the public to understand and engage in the process, and to provide comment at the various stages of the assessment. A significantly reduced number of projects undergoing EA at all means the public will have less say in various types of resource or infrastructure projects that may have local significance.

The report from the House Committee that reviewed our existing CEAA proposes that public participation be “enhanced” and the majority report (written by Conservative MPs) notes that “Public participation during EAs was widely acknowledged as a part of the process for achieving a social licence to operate.” But for that social licence to be valid, the public participation process also needs to be defensible, inclusive, meaningful. The minority reports (written by opposition MPs) also highlighted the importance of public participation.

5. Given the Canadian government promises to be a leader on climate change, why does the 2012 Budget repeal the only Canadian law that required the government to report on its progress in reducing Greenhouse Gases and eliminate an expert advisory body, the National Roundtable on Environment and Economy (NRTEE), which was charged with helping the government to figure out how to make such reductions?

Despite the Canadian government’s insistence that it providing leadership on climate change, there is increasing evidence that the country will not achieve its greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction goals (which have been criticised as too weak).

Prior to Bill C-38, the Kyoto Protocol Implementation Act required the government to report annually on its progress towards reducing GHGs. The repeal of this act was not a surprise, although there was no reason that these changes should be hidden away in a budget bill, in that the government has for several years disagreed with the targets contained in the Act. Whatever one thinks of the Kyoto Protocol and its targets (and we’ve supported them), the fact remains that Bill C-38’s repeal of the Act means that there is now no legal requirement on the Canadian government to report on its GHG reduction efforts. Bill C-38 could have, but did not, enact other climate reporting provisions to replace those repealed.

All of which raise questions about the government’s sincerity in addressing climate change.

6. In 1994, in his role as an MP, Stephen Harper asked how, in the face of an omnibus bill, MPs can “represent their constituents on these various areas when they are forced to vote in a block on such legislation and on such concerns?” Do you agree that omnibus bills reduce the ability of MPs to represent their constituents?

Omnibus bills are not a new practice, but that does not make them a good practice or one that upholds the values of democracy that Canadians hold in high regard. An omnibus (Latin: “for everything”) bill is a proposed law that covers a number of unrelated topics.

Such bills are almost always an attempt to slip controversial amendments past Parliament and the public without adequate scrutiny. They seek to minimize the political damage the governing party must take to advance its policies. Bill C-38 has been an especially egregious example of omnibus law-making: It is more than 450 pages long, contains in excess of 750 clauses and amends nearly 70 laws. And there are many thousands of Canadians that think controversial and significant changes to environmental laws (that make up a full third of the bill) should have been separated out, debated on their own merits, and voted on separately from myriad other provisions in the mammoth bill. With the dozens of laws being amended through C-38, from employment insurance, to old age security, to the Fisheries Act, to an overhauled environmental assessment law, MP's ability to collect and represent their constituents on all issues has necessarily been impaired, and we think that's an erosion of democracy.

That’s our list. Are there other questions that you think we should have included? If you do talk to your MP, post below about how they answered these and any other questions you asked.

By Rachel Forbes and Andrew Gage, Staff Lawyers, West Coast Environmental Law Association