Last week, at the close of the hearings for the legal challenges to the federal government’s Enbridge Northern Gateway approval, Justice Dawson thanked legal counsel for their submissions and added that she could recall, from her days as a lawyer, the feeling at the end of a case when the responsibility shifts from the lawyers who have made the arguments to the judges who must now decide the issues. After about a year and a half working on the Northern Gateway judicial review for Nak’azdli and Nadleh Whut’en First Nations, along with co-counsel Cheryl Sharvit, I certainly felt that shift as the hearing was adjourned and we walked out into the street. Suddenly it didn’t seem out of the question to take a long lunch, and I had a bit of time to reflect on the significance of the past six days in Court.

When I think about the case, what sticks with me most is not a moment during the hearings, or a particular legal argument or issue. Rather, what comes to mind is a conversation that I had in mid-September in Nak’azdli. I had just finished giving a community legal update on the upcoming case, and I was speaking with a Nak’azdli woman who I knew. As we said goodbye to each other, she handed me a stone. She asked if I would be willing to carry it with me into the courtroom during the Northern Gateway hearings, so that there would be a piece of the north there when the case was being heard. I agreed, and the stone was in my pocket when we addressed the Court.

That request has struck me as emblematic of a problem I’ve heard expressed by many people in different ways, something confronted in the Northern Gateway hearings that goes deeper than the case itself: a disconnect between systems of Crown decision-making about industrial development and the people and places that ultimately bear the burden of those decisions.

In fact I almost picture the arguments in the Northern Gateway cases occurring in two layers, the first layer being the specific issues of significant environmental concern, such as responding to malfunctions and accidents (i.e. spills), complying with the protections afforded by the Species at Risk Act, and so on (West Coast has already produced a day-by-day summary of the Northern Gateway hearings, touching on a number of those more detailed issues, which I won’t repeat). The second layer, however, goes underneath the legal details to the core of how we, in a societal sense, make important decisions – what is included and who is heard.

In that regard there was a broad, big-picture distinction between what the two sides were saying in the hearings. On the one hand, counsel for Canada and Northern Gateway spoke a great deal about the details of the process – the number of Joint Review Panel hearings, the weight of the correspondence record, the amount of funding offered to participate, etcetera. While on the other hand, counsel for the Applicants often spoke about not being heard, emphasizing that regardless of the “bells and whistles” of the process, the fundamental concerns they raised and the issues they cared about most deeply – such as consideration of climate change, or respect for Aboriginal title and systems of Indigenous law and governance – were not taken seriously or meaningfully addressed.

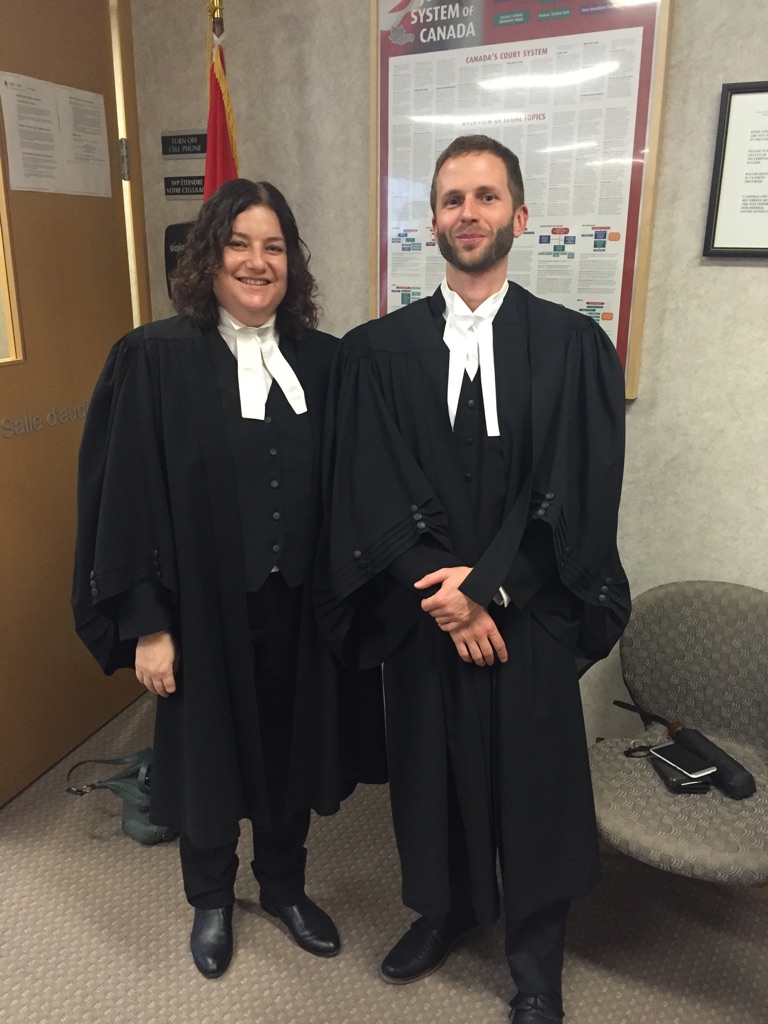

Gavin and Cheryl Sharvit, the dream team. (Photo credit: Cheryl Sharvit)

The Court’s decision in the Northern Gateway cases will be important because it will likely confront some of these issues directly. However, Northern Gateway demonstrates a need for broader reform that goes beyond a single project. Reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in Canada, for example, is not a path that can be pursued on a project-by-project basis. It requires respect and recognition for Indigenous societies, and collaboration to build shared approaches to decision-making. Similarly, as the environmental and human burdens of industrial development continue to add up, managing those cumulative impacts requires processes that focus first and foremost on the health of ecosystems and what levels of overall impact and risk people are willing to accept there, rather than looking narrowly at each project one-by-one as they are proposed.

The federal process that led to the approval of the Northern Gateway proposal is a prominent example of a decision-making approach that has not worked. Sometime in the months to come the Federal Court of Appeal will render its decision in the Northern Gateway cases, but regardless of the outcome, we can and must do better.

No one should have to send a stone 1,000 kilometres across the province, in a lawyer’s pocket, to feel like the land they care about is being represented in decisions that affect it.

Gavin Smith

Staff Counsel

*Note: these comments represent my own views and not necessarily those of any client.