“Regardless of your views on this particular pipeline (we are opposed, in case that wasn’t clear), anyone who thinks their locally-elected government or local First Nations shouldn’t get railroaded by a US corporation just because they have a federal approval should be very concerned about these recent developments.”

That was the concluding line to my recent blog post about jurisdiction and the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain project. The day after it was published, the National Energy Board released two documents: the reasons for its decision to allow Kinder Morgan to bypass some Burnaby bylaws, and the decision on Kinder Morgan’s motion to set up a generic process for resolving local permitting disputes in the future.

The reasons in the Burnaby bylaw issue confirmed what we had previously inferred. In order to apply the doctrines of paramountcy and/or interjurisdictional immunity, the NEB panel had to find that there was a frustration of federal purpose or operational conflict, or impairment of ‘a core competence of Parliament’, ie. the federal approval of the inter-provincial pipeline.

So, while the NEB found that there was no evidence of political interference in Burnaby’s permitting process, they held that the City’s process was “unclear, inefficient, and uncoordinated” which led them to the conclusion that Burnaby’s “unreasonable process and delay…impair a core competence of Parliament”. This, from the regulator who defied the laws of quantum physics in order to meet their own legislative timelines.

Generic process

The decision on the dispute resolution process granted much of what Kinder Morgan asked for: namely a generic process with a 3-5 week turnaround, to ensure that the system is “transparent, efficient and fair.”

The generic process allows for Kinder Morgan to go to the NEB whenever the company feels that local government permits or approvals are taking too long (in this case, “local governments” refers to both provincial governments and municipalities). This is troubling for a number of reasons.

Why this is concerning

Much has been made of the NEB’s 157 conditions, which Kinder Morgan must meet in order to proceed with the project. The company insists that the conditions will address and mitigate concerns raised by local residents, Indigenous Peoples, and other opponents such as municipalities, community groups or businesses. The Federal Cabinet even adopted these 157 conditions without change, despite being told by First Nations and their own Ministerial Panel that the NEB left a lot of questions unanswered.

Indeed, Condition #2 states that “Trans Mountain must implement all of the commitments it made in its Project application or to which it otherwise committed on the record.” This included a commitment by Kinder Morgan to apply for, or seek variance from, all permits and authorizations that are required by law.

Apparently, living up to its commitments was too much for Kinder Morgan, which is why they brought the motion to bypass Burnaby’s bylaws in the first place – to be excused from Condition #2. The generic process is meant to expedite relief from other permits.

Circumventing local laws and getting special treatment

The effect of the generic process is that it gives Kinder Morgan the ability to circumvent local laws and processes by unilaterally deciding what a ‘reasonable’ timeframe for processing permits should be. This means that a local government’s own processes will have to change to accommodate Kinder Morgan’s timeline.

The NEB already started altering local government processes when it required Kinder Morgan to establish ‘technical working groups’ with municipalities in Condition #14. As we saw in the Burnaby bylaw hearing, the working group actually added confusion and delay by changing established municipal processes.

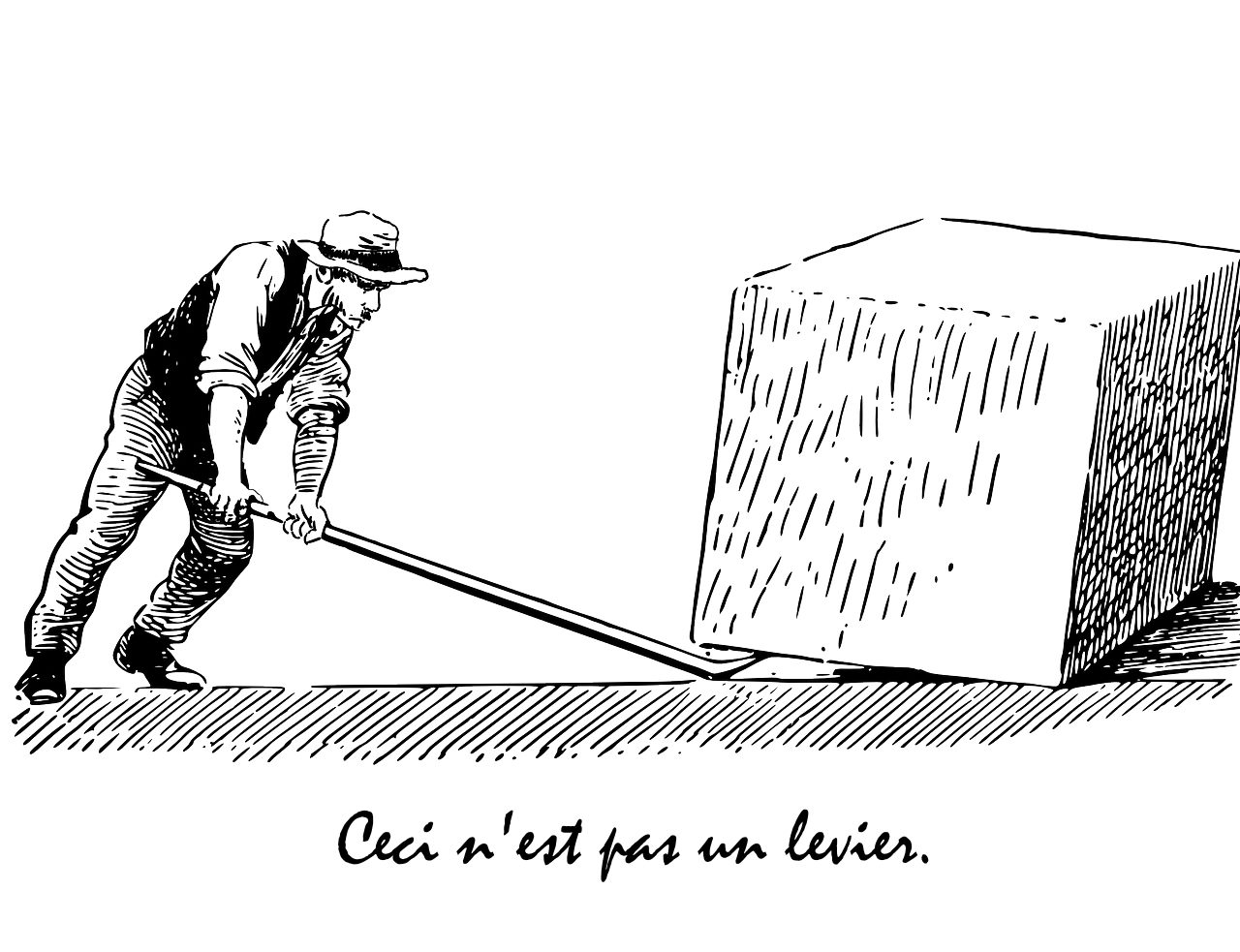

The NEB directed Kinder Morgan and local governments to work towards issuing permits in good faith before using the generic process. But regardless of whether the generic process is even used, it will have the effect of giving Kinder Morgan leverage and special treatment when it comes to processing permits.

As Langley argued to the NEB: “Trans Mountain cannot expect preferential treatment, expedited review, or allocation of inordinate number of staff resources to the [Trans Mountain Expansion Project]. Similar to Trans Mountain, other applicants depend on the timely processing of their applications.”

Chilliwack argued: “[W]e see no other reason for the proposed generic process than to use it as leverage against the City.”

This is of particular concern because this special treatment comes with a cost. Giving Kinder Morgan priority over other permit applications means that other applications will be bumped down the queue. That could be a community centre, a school, a business, or social or market housing development.

While the NEB and Federal Cabinet have determined that Kinder Morgan’s project is in the ‘public interest,’ there has never been a consideration of whether the pipeline is more important than housing, or schools or hospitals.

This is where some Orwellian level doublespeak comes in. On one hand, the NEB states: “the generic process is not to be used as a negotiating tool” (page 8). But then it states: “The Board encourages the Applicant, where reasonable, to provide the Respondent with advance notice of the Applicants’ intent to trigger the generic process, as this may increase the parties’ abilities to move forward efficiently” (page 9).

In other words, they are saying that the giant lever they created should not be used for leverage, except where it should. What?!

Kinder Morgan celebrated the generic process, stating that it would provide certainty to the company’s schedule. But the NEB Panel (through consultation with their lawyers no doubt), left a pressure valve in a clear attempt to insulate from potential appeals – allowing itself the flexibility to make any further adjustments to the generic process if required. So that certainty may not be so certain after all.

Shuts out third parties and First Nations

The entire premise of the generic process is to resolve potential disputes between Kinder Morgan and local governments on permitting issues. But many times, these permits impact other parties too: neighbouring landowners or businesses for example, would have a voice in the local government process. The effect of the generic dispute process is that those third parties could be shut out of the discussion, depriving them of basic procedural fairness.

For example, in a scenario raised by Katzie First Nation and the Province of BC, permits issued by BC could require a duty to consult, seek consent and accommodate affected First Nations. If that process is taking longer than Kinder Morgan wants, and they trigger the generic process, there is no guarantee that the First Nation will be included, and it will have to rely on the Province to assert its rights – which is generally the opposite role taken by the Crown.

Undermines cooperative federalism

Canadian law recognizes the fact that our lives do not fit into watertight jurisdictions, and that laws can and will overlap, with the assumption that they can coexist. This notion of cooperative federalism was embedded in the NEB’s own recommendation and conditions, which required Kinder Morgan to follow local laws and work with municipalities. But the generic process undermines and erodes this fundamental part of Canadian federalism.

For example, many local land use laws incorporate federal Fisheries Act standards to determine appropriate set-back distances to protect fish habitat. This allows for the protection required by federal law to be recognized in provincial or municipal laws, and avoids prosecutions by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), who would not have the jurisdiction to determine zoning laws.

The generic process has the effect of undermining this notion of cooperative federalism by limiting and fettering provincial jurisdiction and processes, and placing timelines in the hands of the proponent.

So, what happens next?

It remains to be seen whether or when this decision will be appealed – the BC government is considering an appeal, and other cities and provinces should also be concerned.

In the meantime, given that this pipeline and tanker project involves the transportation of a toxic, flammable and dangerous product (diluted bitumen) through a high-pressure tube and floating container, shouldn’t we want more safeguards, and not less?