On May 4, 2011 the BC Supreme Court released its decision in Friends of Davie Bay v. Province of British Columbia. The decision, which rejected the Friends’ challenge of an environmental assessment of a gravel pit at Davie Bay, on Texada Island, raises questions as to whether BC’s Environmental Assessment Act is fundamentally flawed. The Friends of Davie Bay have filed an appeal.

The case concerns the claim, by the Friends of Davie Bay (the Friends), that the Act requires an environmental assessment of the proposed Lehigh Northwest Cement limestone quarry and load out facilities in Davie Bay, on Texada Island. As West Coast Environmental Law previously reported on this legal challenge, the case revolved around deciding between whether an environmental assessment is required should be based on how much gravel Lehigh Northwest Cement says that it will produce (and is asking for approval to produce), or on how much it could realistically produce with the proposed infrastructure.

LeHigh Northwest has indicated that it intends the Davie Bay quarry to produce 240,000 tonnes/year, or just below the threshold that would require an environmental assessment. But, it’s building infrastructure that [could] support a much larger mine. … BC Environmental Assessment Office, in response, has stated that it understands the “production capacity” to refer not to the capacity of the on-the-ground infrastructure, but the amount of gravel extraction that LeHigh Northwest has requested permission for in its applications to the Ministry of Energy and Mines.

As the Friends argued, a mining company could understate its initial capacity, thereby avoiding an environmental assessment, and later apply to increase its production without triggering an assessment. The judge, the Honourable Mr. Justice Voith, understood this concern, stating:

“One could, in concept, develop a significant mine with a modest level of initial production. That level of production would fall below the ‘production capacity’ threshold for ‘New Mines’. Thereafter, if the proponent chose to increase that initial level of production the project could again escape a mandatory environmental assessment if its initial physical footprint adequately accommodated the increased level of production.”

However, Voith J. found that he needed to focus not on the “correct” definition of “production capacity”, but rather whether the EAO had adopted a “reasonable” interpretation when it found that LeHigh’s “production capacity” was 240,000 tonnes/year.

Justice Voith found that the EAO’s interpretation was reasonable on two main grounds:

- The focus on the production capacity to be authorized – as opposed to the capacity that an operation could sustain – is simpler, and more easily applied; a company, government agencies and the public can easily determine whether an environmental assessment will be required, without a complicated assessment of what a mine’s actual capacity may be. The judge wrote:

“The proponent of a project must be able to plan its operations with certainty. To do so it must be able to ascertain whether its intended project falls within the Environmental Assessment Act and the Reviewable Projects Regulations... The public must [also] be satisfied that the Environmental Assessment Act is being adhered to and that the public interest is being properly safeguarded. This object is enhanced if the relevant criteria … are transparent and readily understood. … These disparate interests are also most effectively reconciled if [the legal requirements yield] a discrete and consistent result. They cannot realistically be achieved if [the law] requires a detailed consideration of the myriad unspecified and hypothetical factors that may be relevant to the ‘production capacity’ of any given project".

- The Minister has the flexibility to declare that an environmental assessment will be held on a project that falls below the threshold; Justice Voith believed that the power of the Minister to intervene favours a simple definition of “production capacity”, since the Minister may intervene when other factors favour a more complicated approach.

We are troubled by Justice Voith’s decision. With all due respect to the judge, we do not believe that the ability of the Minister to order an environmental assessment of a project – a power which is rarely exercised – deals with the problem of projects which are incrementally expanded to avoid an environmental assessment. Despite the simplicity of the EAO’s interpretation, we do not believe that the environment is well protected by this approach.

If Justice Voith’s decision stands, it means that there is a significant flaw in the Environmental Assessment Act regime. If industry does not meet the threshold to ‘trigger’ an environmental assessment, they can still build projects that have the potential for a higher production capacity. They can then avoid future environmental assessments by increasing their actual production incrementally.

By Andrew Gage, Staff Lawyer, with assistance from Katrina Andres, Legal Intern.

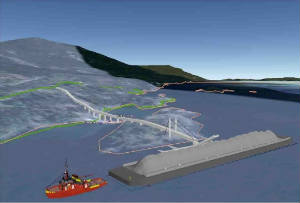

Photo courtesy of Friends of Davie Bay, generated with Google Earth.