Oil spills, plastic waste, sewage, dumping, ocean heating and acidification, overfishing, whaling, harmful fishing, anchoring, engine noise, pile driving, submarine cables, seismic surveys, offshore oil drilling and wind development, wave energy, container shipping, and cruise ships. If you were the ocean, wouldn’t you want a break?

Think of all the threats that Pixar’s famous clownfish Nemo faced as he travelled across the ocean to find a home. Shouldn’t there be safe resting spots along the way?

Clownfish Nathan Rupert via Flickr Creative Commons

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are designed to do just that. These wildlife parks in the ocean, called Hope Spots by oceanographer Sylvia Earle, provide respite from the onslaught of human activities that burden the increasingly exploited and noisy ocean.

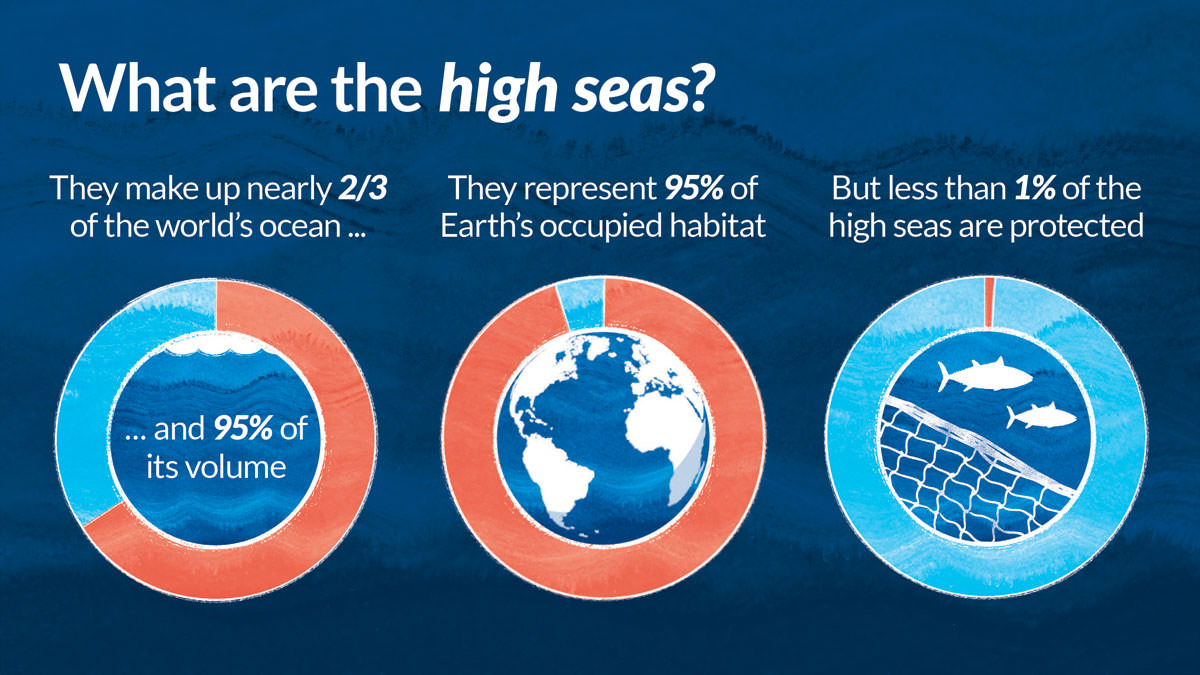

Countries have made great strides in protecting their ocean areas with MPAs, but two-thirds of the ocean lies on the High Seas, outside national boundaries and beyond the ability of any individual country to protect. In the ‘lawless’ High Seas, unsustainable fishing, shipping and mineral exploitation threaten some of the world’s most pristine ecosystems.

There is reason for hope, too. A new treaty being negotiated at the United Nations will change the rules for the High Seas and may allow us to finally protect the incredible diversity of life in one of the world’s last frontiers.

A flurry of change has accelerated ocean protection. Aided by global targets like the one to protect at least 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas by 2020, we’ve seen tremendous increases in national MPAs. For example, Canada jumped from protecting approximately 1 per cent of its ocean areas with MPAs to over 13 per cent in just four years.

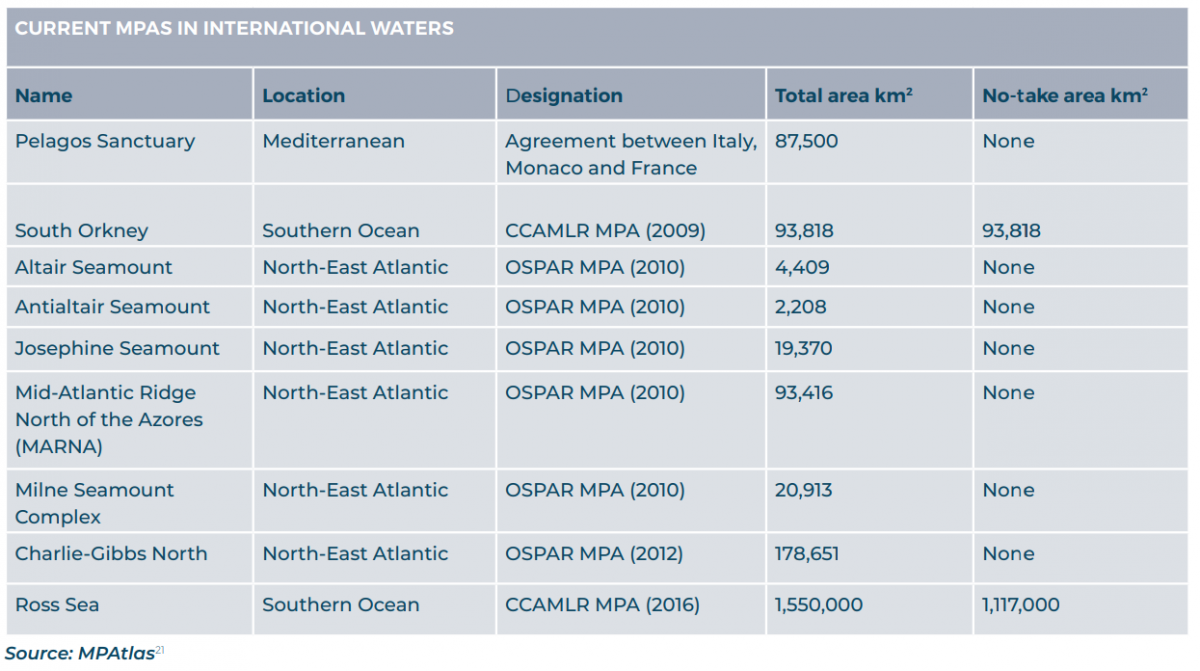

Scientists and conservationists alike are now calling for at least 30 per cent protection by 2030. The world currently sits at about 7 per cent marine protection but if you also include areas that have been committed to but still not implemented, only 1.2% is on the high seas, so great swathes of this ocean area need to be turned into MPAs to reach that target.

From seamounts to seabed minerals, from krill to sharks, from cetaceans to coral – there is no shortage of potential High Seas MPAs. Candidate areas for High Seas MPAs span the globe, such as the ‘White Shark Café’ between Baja, Mexico and Hawaii where great white sharks congregate to feed and rear. Effective High Seas MPAs can offer immense benefits by restricting the most damaging and pervasive human activities.

Chart by Greenpeace (in 30x30: A Blueprint for Ocean Protection report)

The High Seas are crying out for protection in two places in particular. The first is East Antarctica where the threats of climate change and the expansion of factory fishing of krill into the region threatens the food chain of the marine area surrounding the continent. The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources has been unable to establish MPAs in this area due to opposition from fishing nations. The second is the vast Sargasso Sea in the North Atlantic Ocean, the golden rainforest in the sea, where floating Sargassum seaweed provides a home for wahoo, tuna, billfish and other fish species as well as cetaceans, sea turtles, and sharks. The endangered European eel that spawns in the Sargasso Sea travels across the Atlantic for centuries, even lending its name to the cathedral city of Ely near Cambridge in England.

High Seas MPAs do currently exist, agreed to by a small number of nations under a regional treaty rather than by the entire global community, however, with the exception of the Ross Sea in Antarctica, none of these MPAs prohibit extractive activities entirely. The chart from this recent report demonstrates the problem.

Image credit: Global Fishing Watch, 2018

For decades, experts have been calling for an international treaty to fill the legal gap in High Seas protection. In 2017 the UN General Assembly finally agreed to negotiate a treaty referred to as an “internationally legally binding instrument for biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction” or ILBI for BBNJ – yes, the acronyms in this field are truly horrendous!

However, key issues still need to be resolved in these negotiations. How should MPAs be defined for the purposes of High Seas protection? Who will designate these areas? How will other treaty bodies and international and regional bodies be involved? What criteria will be used to designate MPAs? Will these new MPAs be permanent and how will they be monitored and enforced? The list of unanswered questions goes on.

To avoid the empty promise of ‘paper parks,’ where business continues as usual, the ocean needs places of true refuge from human activities. The most effective MPAs are large, well-enforced, permanently legally protected and ‘no-take’, allowing no extractive activities whatsoever. In such circumstances, depleted marine life has the chance to regenerate and ocean ecosystems can flourish.

A draft text of the High Seas treaty exists. Many issues remain to be resolved – from the definition of MPAs, which must be primarily aimed at conservation, to the procedures for identifying and designating MPAs. Progress has been made and global opinion is coalescing around enhanced protection for the ocean that sustains us all with food, transportation and resources, beauty and spiritual solace.

Negotiators were poised to resume their task at the UN in March, but had to postpone what was supposed to be the final negotiating session due to the coronavirus. The UN General Assembly will decide when the session will resume and has pledged that it will start on the earliest possible available date.

In the meantime, here is some advice for the treaty negotiators: take a deep breath. Thank the ocean for its essential ecosystem services. Enact strong global rules to protect life under water on the High Seas on our blue planet. Give Nemo a home!

Top photo credit: Kyle Mortara via Flickr Creative Commons