Earlier this year, West Coast Environmental Law became aware that British Columbia's Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy has quietly set up a Twitter account, @ComplianceBC. As part of its mandate to enforce environmental laws, the BC government posts updates to this social media channel sharing recent environmental violations and penalties levied against polluters, poachers and other offenders.

This was the most recent tweet when we started researching this post (a couple of months back):

Valley Wide Meats in #Enderby received a $6,450 administrative penalty for non-compliances under the COP for Slaughter and Poultry Processing. They didn’t provide slaughter production records & daily wastewater generation. For a second time. https://t.co/86FV8gEhSr pic.twitter.com/Cbj672ewSY

— Environmental Compliance BC (@ComplianceBC) September 14, 2022

Note the “For a second time.” Looking back through the earlier tweets we saw that many of them mentioned repeat offences. This blog post looks at the way that the government is currently addressing non-compliance, and whether more could be done to dissuade offenders from re-offending.

Administrative penalties are the penultimate enforcement tool

The focus of the @ComplianceBC Twitter account’s tweets is on administrative penalties, mostly under the Environmental Management Act (BC’s main law dealing with pollution).

Historically the BC Environment Ministry has had two main types of penalties at its disposal: tickets (usually for a few hundred dollars) or charges (which are tried in court, often requiring significant time and resources). But as we’ve written in the past, administrative penalties are a relatively new tool intended to give the Ministry more options to deal with offenders:

Administrative penalties fill the gap between charges and tickets. They give officials within the Ministry of Environment the authority to decide on and impose penalties in the course of their own “administration” of the Act – without needing to turn to courts. Unlike tickets, the penalties can be significant, but can also be tailored to the individual circumstance. Since they don’t need to involve complicated, expensive and scarce court resources, they are more likely to be used by the Ministry of Environment.

The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy has the power to impose administrative penalties after conducting a process to hear from the alleged offender. The penalties can carry serious financial consequences, but still lack the teeth and social stigma associated with laying charges and taking an offender to court.

The Twitter account attests to the recent increase in the usage of administrative penalties as a key tool in the Ministry’s toolbox to address non-compliance. However, we are concerned that the Ministry seems not to be using other tools against repeat offenders, such as charges, even where the administrative penalties do not appear to be having any deterrent effect.

Examples of repeat offenders

The BC government maintains a Natural Resources Compliance and Enforcement Database (the “Database”) containing details of its efforts to enforce environmental laws and other statutes. We used this database to take a look at how often the data showed a pattern of repeated offences.

Unfortunately, a review of the Database and the administrative penalties profiled on the Twitter account reveal a history of non-compliance under the Environmental Management Act. Eight of 27 offenders (almost 1/3) that received administrative penalties in the past 6 months, have had a previous administrative penalty and/or charge laid.

We note that the offenders that had no previous administrative penalties were not necessarily in compliance in the past either. In many cases they had received warnings, orders or other types of compliance and enforcement action. However, this post focuses on the limits of administrative penalties in preventing offenders from breaking the law again.

Valley Wide Meats and its owner Richard Yntema are an example of a repeat offender recently profiled on the Twitter account. Richard Yntema runs a farm in the North Okanagan raising non-native deer, reindeer and bison since 1991, and has had a storied history of environmental non-compliance. Mr. Yntema has previously violated the Wildlife Act and has also received repeated fines and penalty actions from the federal government under the Health of Animals Act beginning in 2015.

On November 13, 2020, Mr. Yntema was issued an administrative penalty for non-compliance under section 109 (6) of the Environmental Management Act (EMA) for failing to produce records of production and discharge flow rates of waste from his meat processing facility over the period from March 8, 2019, to June 25, 2020. This penalty did not come out of nowhere; the Ministry had previously spoken to Mr. Yntema regarding his non-compliance and lack of records and had even offered to help in establishing a record-keeping system. Mr. Yntema had refused the help and continued providing no records, in contravention of his permit.

Mr. Yntema appealed the administrative penalty to the Environmental Appeal Board (EAB), which found that while he did not commit that particular offence under the EMA, he had violated section 3 (d) of the Code of Practice for the Slaughter and Poultry Processing Industries, B.C. Reg. 246/2007 (the Code), which requires records to be kept for 10 years and provided to an inspector when requested. The EAB lowered the penalty amount from the initial $6,300 to $3,525.

However, this fine does not seem to have had the intended effect of deterrence as Mr. Yntema was issued another administrative penalty on June 29, 2022, for contravening section 3 and section 6 of the Code. Mr. Yntema did not provide information regarding live weight killed per year or the volume of wastewater discharged per day, even after the environmental officer extended the deadline for submissions at their discretion.

Furthermore, there was no installed measurement device for wastewater at Mr. Yntema’s facility, owing to his refusal to install one, which meant he had no records of flow monitoring. This violation of the Code led to the Ministry issuing a penalty worth $6,450, to which $450 (15% of the previous penalty of $3,525) was added for having a repeat contravention.

Another example of a recent repeat offender is Nicola Mining Inc., a mining company that boasts about its commitment to the environment and water, had multiple administrative penalties levelled against them for (among other things) discharging drainage water containing pollutants which exceeded the allowed limits, and failing to provide a drainage plan in February 2020. They also failed to comply with terms of their permit requiring sediment sampling on the site and benthic invertebrate sampling. Two years later, in July and August of 2022, the company received more administrative penalties totalling $59,000 – again for non-compliance in relation to many of the same contraventions they had committed previously.

Skookumchuck Pulp Inc. is a further example of administrative penalties failing to deter repeat offences. The paper mill has a history of illegally discharging waste into the environment and other non-compliance starting in 2018, leading to administrative penalties beginning in 2019. The company has received administrative penalties on nine different occasions, totalling $174,690 as set out in the following table:

| Date | Fine Amount (dollars) |

|---|---|

| July 9, 2019 | 2,250 |

| Jan 22, 2020 | 8,640 |

| Jan 19, 2021 | 52,000 |

| Apr 20, 2021 | 58,800 |

| Mar 3, 2022 | 4,500 |

| Mar 29, 2022 | 6,500 |

| Apr 13, 2022 | 8,500 |

| May 10, 2022 | 15,000 |

| May 18, 2022 | 18,500 |

| Total to date | 174,690 |

Although the mill has been fined a substantial amount of money through administrative penalties, this did not prevent them from committing similar offences. The penalties issued to the mill were highlighted in an article published May 6, 2021, which expressed hope that a change in ownership would bring improved compliance, after the company was bought out by Paper Excellence. The most recent administrative penalties received by the mill in 2022 were in respect of violations that occurred before the purchase.

Similar behaviour can be seen in the case of Mackenzie Pulp Mill Corporation, which received multiple administrative penalties from 2018 to 2020 for discharging pollutants above the allowed limit and for not maintaining their recovery boiler stack. Again, many of the contraventions were repeated later on, suggesting that the penalties imposed did not have the intended deterring effect.

The company received an administrative penalty totalling $81,100 on July 17, 2018, for failing to comply with maintenance of works and with their authorized discharges. The company would subsequently be issued another administrative penalty on March 8, 2019, totalling $92,500 and on July 2, 2020, totalling $106,500 for non-compliance of repeat contraventions. The only reason the administrative penalty in 2020 was not higher was that the company had shown efforts to increase its compliance, leading to a reduction in the penalty.

Options to deal with repeat offenders

The repeated non-compliance of some offenders after receiving administrative penalties makes one thing clear: in some cases, more needs to be done to ensure compliance with environmental laws and regulations. While the larger fines placed on non-complying businesses will encourage some to comply going forward, it has not affected all businesses in that manner. In those cases it seems like the penalties are being absorbed as a cost of doing business.

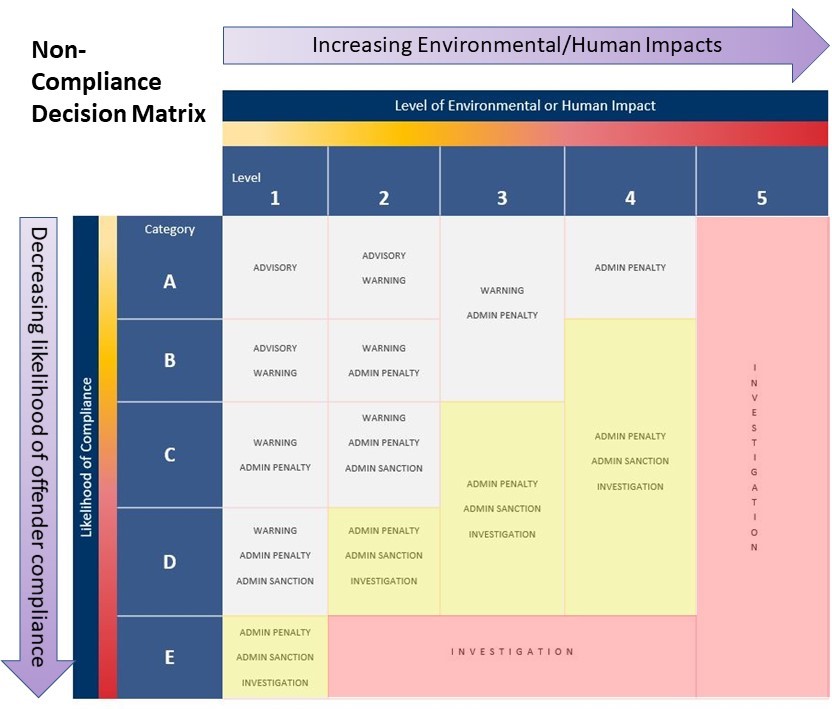

BC Ministry of Environment & Climate Change Non-Compliance Decision Matrix (with yellow and red shading added by WCEL)

The Ministry bases its decisions on when and how to ticket, issue administrative penalties or charge environmental offenders using a “Non-Compliance Decision Matrix” set out in the Ministry’s Compliance and Enforcement Policy and Procedure. We added red and yellow shading to the Matrix to highlight the types of offences considered most serious. The Ministry has three main tools available to deal with repeat offenders. They are:

- Administrative penalties – significant financial consequences imposed by the Ministry;

- Administrative sanctions – the Ministry revokes or suspends the permit or permission to pollute, effectively making any discharge of waste from the operation illegal; or

- Investigation and referral to Crown Counsel (government lawyers) for charges to be laid, or other enforcement action.

The Matrix suggests that offences that involve the most serious environmental consequences, or offenders who are actively lying to or working to frustrate law enforcement, should always be investigated for possible charges. (See the area shaded in red in our adapted matrix).

However, more broadly, the Matrix directs Conservation Officers to consider these three options in cases involving either serious harm or potential serious harm to the environment or human health, or where there is a low likelihood of compliance. (The area shaded in yellow in the matrix).

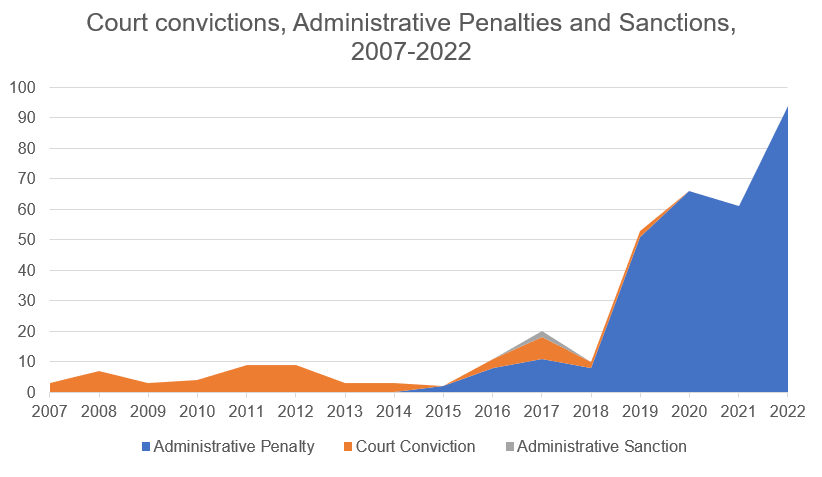

As we’ve written previously, BC has suffered for many years from inadequate enforcement of environmental laws, especially in relation to industrial polluters under the Environmental Management Act. A review of enforcement action recorded in the Database reveals that administrative penalties have recently begun to fill this gap (which is good news, see the graph below). But now, these administrative penalties represent the vast majority of serious enforcement efforts under the Environmental Management Act, with court proceedings used rarely and administrative sanctions almost never.

This raises two questions:

- Are there ways that administrative penalties can be used more effectively to achieve compliance?

- Would more extensive use of administrative sanctions and charges (leading to convictions) through the courts be more effective in addressing repeat and serious offenders, and, if so, why are they not being used?

How to use administrative penalties to achieve compliance

While the increased usage of administrative penalties is an improvement on issuing warnings or minor tickets, the pattern of repeat offenders shows that the Ministry’s approach needs some work. If offenders frequently continue to offend or re-offend after receiving an administrative penalty, then damage to the environment or human health, or the risk of such damage, also continues.

The Database includes a “penalty assessment” form, which shows the range of factors considered in the current system used by the Ministry to calculate administrative penalties. The two factors particularly relevant to repeat offenders are consideration of “c) Previous contraventions, penalties imposed, or orders issued” and “d) Whether contravention or failure was repeated or continuous.” Factor c) looks at whether the offender has contravened the Environmental Management Act previously in any way, while factor d) specifically looks at whether the offender has previously violated the particular provision they are now violating.

However, while these factors are apparently considered by the Minister, we could not find any public policy document or guidance that provided any details of how they are applied. Instead we attempted to infer the policy based on the administrative penalties that had been imposed, but they were not entirely consistent.

For instance, factor c) added an extra 15% to the second administrative penalty for Mr. Yntema issued on June 29, 2022. However, for Skookumchuck Pulp Inc.’s administrative penalty on May 10, 2022, that same factor assigned an additional 10% to the penalty, despite multiple prior penalties.

In regards to factor d), the penalty issued for repeating the same contravention, the calculation has largely remained consistent, amounting to 30% of the base penalty for both Skookumchuck Pulp Inc. and Mr. Yntema. But this calculation has not increased with ongoing non-compliance.

To discourage repeat offences, whether under the same permit or for the same contravention, the Ministry should have a publicly transparent penalty policy which ensures that penalties increase dramatically with ongoing non-compliance.

If companies face increased monetary penalties for repeated non-compliance, and they are made aware of this, they may be more motivated to make any changes needed to remedy their non-complying behaviour and fall in line with their permit.

Convictions and administrative sanctions

As discussed above, convictions and administrative sanctions represent an increasingly small percentage of enforcement actions taken under the Environmental Management Act. In part this is because of the increase in administrative penalties (which is actually good news). But the fact is the use of administrative sanctions is only found once in the Database, which contains compliance actions taken since late 2006 (technically twice, but both times were in relation to a single project in 2017), while convictions under the Act appear to be dropping over time. Indeed, to date in 2022 the Database does not report a single conviction (although it is possible that this is due to information not yet being added to the Database).

There are good reasons that the Compliance and Enforcement Policy requires that charges (leading to convictions) or sanctions be used in cases where the environmental/human health impacts of an offence are serious, or where there is reason to believe that the offender is unlikely to comply.

Convictions in a court carry with them a social stigma as well as still larger penalties, including the potential for jail time (although in practice judges have been reluctant to send environmental offenders to jail).

Administrative sanctions remove the legal authority of the offender to pollute going forward, either temporarily or permanently. In the context of industrial pollution under the Environmental Management Act this may be tantamount to shutting the offending business down. We suggest that this is quite appropriate when dealing with a polluter that is unable or unwilling to comply with the law.

But far from being the prominent tools contemplated by the Act, charges/convictions and administrative sanctions are almost never being used, even for the most serious repeat offenders. For the last five years of data for offences, 19 administrative penalties were handed out for every 1 court conviction. There were no administrative sanctions issued.

Why are these other tools used so rarely, particularly in the face of repeated offences?

In the past we have been told that the cost of court proceedings, and the fact that the court system is backed up, has dissuaded the government from laying charges under environmental offences (resulting in fewer convictions). It is obviously concerning if environmental offenders are escaping being charged because of backlogs in the criminal justice system.

However, while this is doubtless a factor, it is ultimately a question of priorities. A dig into the Database suggests that at least some environmental convictions are being obtained, but not under the Environmental Management Act.

In the past five years there have been only four actual convictions under the Environmental Management Act, subject to any last-minute additions for 2022. This does not count what appear to be cases in which people appealed tickets for fines to the BC Provincial Court, which the Database misleadingly records as a conviction.*

The four convictions involve three offenders, as one trial resulted in convictions for two offences. However, none of these offenders (one corporation and two individuals) appear in the Database as having offended previously, although at least one offence involved a high level of harm to fish and human health.

During the same period, under a different statute, the Wildlife Act, there were 27 convictions over the same period, all against individuals, again not counting the many individuals who appealed tickets.*

Although this is a very small fraction of the enforcement action taken under both Acts, it is clear that the government does have the resources to invest in some charges under environmental statutes, but that offenders under the Environmental Management Act, and especially the repeat offenders discussed in this article, do not appear to have been prioritized.

A similar issue comes up in relation to administrative sanctions. As mentioned, the Database records administrative sanctions being used only in 2017 when Environment Minister Mary Polak cancelled the waste discharge permit for the politically controversial Cobble Hill Holdings contaminated soil facility. By contrast, the Database records over 3,500 examples of administrative sanctions under the Wildlife Act, the vast majority of them involving the suspension or cancellation of hunting licences.

In both cases, this raises questions about whether the government is able and/or willing to bring out the big guns when it comes to industrial polluters. There is no doubt that an action that could impose financial hardship on, or even shut down a business, has greater political consequences than proceedings against individuals. It is also true that businesses may have the resources to fight their charges in court.

However, the environmental consequences of ineffective enforcement may be significant. We suggest that if the government wants to stop offenders from re-offending, it needs to treat industrial pollution more seriously.

Conclusion

The Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy needs to tackle the issue of repeat offenders under the Environmental Management Act. These offenders can cause ongoing damage to the environment and public health, as well as undermining public confidence in the environmental law system.

While the increased usage of administrative penalties is encouraging, more has to be done to tackle repeat instances of non-compliance. The Ministry could start by prioritizing other tools and reviewing its penalty assessment criteria and its decision-making matrix to make repeat offences more serious and costly.

* The Database does not differentiate between court proceedings where charges were laid and cases where someone issued with a ticket appealed the ticket. In the latter case the Database sometimes, although not consistently, lists both a ticket and a conviction in the same amount on the same date. Since tickets are typically for less than $1000, we have assumed in the above analysis that any penalties of less than $1000 were tickets, while amounts over that amount were the result of charges being laid. If our assumptions that penalties of $1000 or less are the result of the appeal of tickets, rather than charges laid, then it is possible that the number of convictions is somewhat higher than reported in this post. However, this would raise additional questions as to why cases involving relatively modest penalties were being pursued through charges and convictions.