Can you imagine waking up in the morning, looking out the window and being annoyed that your view is blocked by a green leafy tree? If you live in the City of White Rock and the tree happens to be on city property you can now just apply to the City to have that eyesore removed and your view of the ocean (or whatever view you happen to look out upon) restored.

I’m being a bit flippant, but a current controversy in White Rock is an important reminder: trees benefit all of us and our governments need to recognize that.

In White Rock the issue has come to a head over a dispute between residents of Royal Avenue. Home owners on the north side of the street want trees that block their view removed. Home owners on the south side want those trees left in place. And thanks to a new city policy, any property owner can apply for the removal of healthy trees on city land that block their view. After initially turning down the application because of objections from home owners on the south-side of the street (Doug and Karen Ellerbeck), on January 24th the City Council allowed an appeal by the “we-want-our-view” North-siders – and ordered the trees removed, and slow-growing replacement trees planted (which won’t compromise the view).

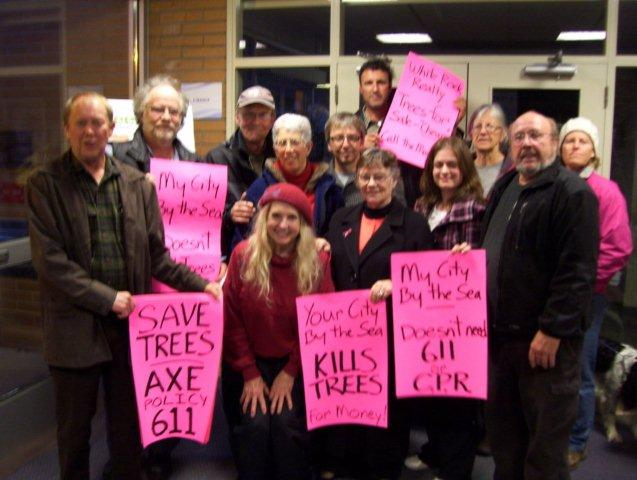

The decision has resulted in protests by the Ellerbecks and other residents to try to save the trees, fears from some residents that the policy will result in wide-spread cutting of city trees, and a promise by the City to re-examine its policy on such tree removals. Of course in the meantime the policy is still in place, and the trees on Royal Avenue are still facing the axe.

The decision has resulted in protests by the Ellerbecks and other residents to try to save the trees, fears from some residents that the policy will result in wide-spread cutting of city trees, and a promise by the City to re-examine its policy on such tree removals. Of course in the meantime the policy is still in place, and the trees on Royal Avenue are still facing the axe.

The value of the trees

White Rock’s Policy 611 – Tree Management on City Lands – while affirming that trees should be left standing “where practical,” nonetheless allows anyone who has property within 25 metres of a tree located on city lands to apply to have that tree removed if it blocks their view.

Most municipalities allow for the removal of trees where they pose a safety hazard or are unhealthy. Sometimes trees are removed on the basis of dubious assertions of risk or health, but nonetheless there is a recognition that healthy trees should be left standing. And, ironically, White Rock’s Tree Management Bylaw, which regulates the cutting of trees on private land (and does not apply to city-owned lands), recognizes this value:

WHEREAS trees provide an essential environmental function contributing to a clean air environment as well as providing habitat for birds and wildlife;

AND WHEREAS Council considers it is in the public interest to provide for the conservation and propagation of trees, and the regulation of their removal and replacement;

This is not to imply that a tree on private land could never be removed due to viewscape concerns, but the bylaw implicitly recognizes that it is balancing such tree removals against the environmental value that the Bylaw protects.

White Rock also recognizes that trees provide value to the community in other ways: its Integrated Stormwater Management Plan calls for greater urban tree cover as a way of controlling run-off from heavy rains: “One of the most basic things that could be done to improve stormwater management is to increase the amount of tree cover in White Rock.”

By contrast, Policy 611 makes no reference to the environmental or community values associated with trees (the word environment does not appear once in the policy), and the criteria listed for determining whether a tree should be removed focuses on the competing demands of neighbours, including:

- In order to be considered for removal, the tree or trees must meet [one of] the following criteria: … the tree is impeding views. …

- the proposed tree removal must not adversely impact privacy, screening or shading for a neighboring property owner, unless that they have no objections to the tree removal.

- the “nuisance tree” criteria must be supported by sufficient evidence, including photographs in order to determine the degree or type of nuisance, where the accumulation of falling leaves or evergreen needles only does not qualify as a nuisance.

So, in other words, the policy does not require any consideration of the value of the tree to the community or the ecosystem, let alone to any intrinsic value of the tree.

The value of trees to a community are many – to the point that some city planners and architects have taken to referring to trees as “green utilities.” They shade houses and clean the air. Realtors report that property values in communities with more trees are higher. In the urbanized and agricultural portions of the Lower Mainland, the David Suzuki Foundation and Pacific Parkland Foundation reported last week that trees provide over $69 million worth of air pollution removal; when you extend that to include the watersheds feeding into the Lower Mainland, the value of this service jumps to almost $409 million. This is consistent with studies elsewhere: New York city calculates that its trees contribute about $122 million a year to the City, while D.C. puts the value of its trees (on a total value basis) at over $3.5 billion.

The value of trees to the environment are also many, from regulating water flow to habitat for birds and wildlife. And, of course, there is the radical notion that a tree has benefit and worth in itself.

White Rock’s policy utterly fails to address these broader public values. Instead the dispute on Royal Avenue came down to consideration of the viewscape of one set of neighbours against the privacy claims of another. Council is quoted as saying that it “has an obligation… to preserve what people had when they came here,” but that seems to refer to their viewscape, rather than their trees.

The Supreme Court of Canada has said (quoting an earlier Ontario Court of Appeal case concerning the protection of trees on a highway) that:

In our judgment, the municipality is, in a broad general sense, a trustee of the environment for the benefit of the residents in the area of the road allowance and, indeed, for the citizens of the community at large.

What this means is that White Rock is responsible to the whole community in its decisions about trees. It cannot just balance the interests of one property owner against his or her neighbour in making decisions about trees.

And municipalities, and the public, everywhere should guard against policies that ignore the true, intrinsic value of trees.

By Andrew Gage, Staff Lawyer