When the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations (FLNRO) tries to detect violations of BC’s forest laws, do they put their efforts into detecting violations by large logging companies or small-scale operators? It turns out that small-scale operators and individuals get over half of the attention of government inspectors, while large-scale logging companies are only the target of about 20% of the government’s inspections, despite holding the logging rights to around 70% of the province’s forests.

The context

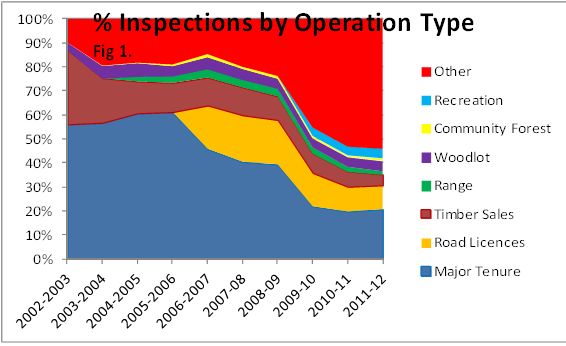

Readers of Environmental Law Alert will recall that the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, over the past decade, has also dramatically scaled back the overall number of inspections conducted (from 21,225 to 8117 from, 2002 to 2012). In a recent Environmental Law Alert we examined this drop in inspections and asked how it was possible that this dramatically reduced number of inspections was still detecting similar levels of non-compliance with its statutes, but was also collecting far fewer fines in connection with those violations. At the time, we noted that the Ministry did appear to be focusing its inspections on “other licensees”, non-tenure holders, and that this might be a partial explanation for the discrepancy.

One factor may be the Ministry’s more targeted approach to investigations. Interestingly, in recent years a larger portion of the investigations have focused on “other licensees/non-tenure holders” – a category which includes many small operators and individuals who are being charged for operating on the land-base, and which has a higher level of non-compliance than larger industrial operators. This shift may help explain some of the increased detection of non-compliance. …

In addition to using fewer [Administrative Monetary Penalties, which carry with them more significant fines than tickets], the government seems to be issuing them for smaller amounts in recent years.

Some of this may be to the shift, mentioned above, towards inspecting more small operators and non-tenure holders (against whom tickets will frequently be the most appropriate enforcement tool).

On reviewing these figures further, it appears that this shift is even more dramatic than we suggested, and we can confirm that this shift seems to be a major factor in the reported compliance and enforcement figures, and deserves its own blog post.

The trends

A decade ago the Ministry focused 60% of their inspections on large logging companies holding major tenures (logging rights), which cover approximately 70% of the province’s forest lands. However, inspections in relation to major tenure licences has dropped to about 20% in 2011-12 (the most recent year for which figures have been released). Conversely, inspections of “other” users of the forest land base have risen from 10% of the inspections to almost 50%. This “other” category includes a range of small forest users, such as: “Other licensees and non-tenure holder statistics involve: Licences to Cut, Special Use Permits, Free Use Permits, Christmas Tree Permits, Private Lands, Log Salvage, Small Scale Salvage and Non-Tenure Holders.”

The Compliance and Enforcement reports provide figures on the inspections of many different types of forestry operations. The relative percentages of each are a bit difficult to figure out, since the Ministry has broken our new categories over time. Notably, road licences have been inspected separately since 2006-2007; previously many of these inspections would have been included in major tenures, boosting the numbers in that category somewhat. Similarly, Recreational users were included in the “other licensees/non-tenure holders” category until 2009-10, when the Ministry began reporting  recreational inspections separately (with those figures included, almost 60% of the 2011-12 inspections related to “other”/recreational users).

recreational inspections separately (with those figures included, almost 60% of the 2011-12 inspections related to “other”/recreational users).

However, the trends are clear – the percentage of inspections dedicated to detecting non-compliance among “other licensees/non-tenure holders” has increased dramatically, while every other category has either stayed roughly the same or declined.  This can be seen both in terms of relative percentages (figure 1) and overall number of inspections (figure 2).

This can be seen both in terms of relative percentages (figure 1) and overall number of inspections (figure 2).

Why this shift?

The Ministry has said that it is focusing its inspections – to allow it to detect violations more effectively. And from a superficial perspective the enhanced focus on other users makes sense. Other licensees/non-tenure holders, and recreational users, are historically about 2.7 times more likely than major licensees to be found to be in non-compliance per inspection (and almost 3 times as likely to have formal enforcement action result).

But a closer look raises significant questions about this approach.

First, while the “other” forest users have the highest non-compliance rate historically, there are several other categories of forest operations that have similar historic, and in some cases levels that are currently higher, of non-compliance (measured in terms of non-compliance or enforcement action taken per inspection conducted), and the Ministry has not increased inspections for these operations.

In 2011-12 woodlot licences, road licences and range licences all had non-compliance rates that were higher than the “other category” (including a staggering almost 60% for woodlot licences), but represented a small portion of the inspections in 2011-12 (about 4% in the case of woodlot licences). Rising non-compliance rates can be seen in timber sales licences as well, and, arguably if less dramatically, major tenure holders. See figure 3 for an idea of non-compliance rates year by year (click the graphic if you want a more cluttered/detailed version with all operation types included).

The trends are similar if you focus on formal enforcement actions (as opposed to all compliance activities), with an apparent increasing trends in formal enforcement actions (ie. tickets, AMPs and formal warnings) used per inspection for woodlots, major tenure holders and timber sales, and apparent decline in enforcement action per inspection taken against “other”, range licences and possibly road licences. Click the graphic or here for a more cluttered/detailed graph with all data included.

The trends are similar if you focus on formal enforcement actions (as opposed to all compliance activities), with an apparent increasing trends in formal enforcement actions (ie. tickets, AMPs and formal warnings) used per inspection for woodlots, major tenure holders and timber sales, and apparent decline in enforcement action per inspection taken against “other”, range licences and possibly road licences. Click the graphic or here for a more cluttered/detailed graph with all data included.

In our view, these trend lines may indicate that inspections in these areas are too low to provide an adequate deterrent.

Second, the refocusing ignores the fact that major tenure licence holders manage massive areas of the province. It seems at least plausible that their non-compliance, even if less in number, may affect a larger area, and have a greater environmental impact.

Indeed, it seems likely that this is a major reason that fewer and fewer administrative penalties are being used (which are intended for major problems), and for the expanded focus on minor tickets. As noted in our last post, the amount of money collected from fines under BC’s forest laws has plummeted from $561,511 in 2002-03 to $72,585 in 2011-12.

And finally, there are the unfortunate optics of going after small operators, while ignoring large-scale operators. Major Tenures currently cover about 70% of the province’s public forest lands, and yet are the focus of 20% of inspections. While compliance and enforcement resources should be put where they will do the most good, and people who fall into the “other” category of enforcement should not get off scott-free, it does appear that there is a failure to effectively enforce BC’s forest laws against other types of forest users.

Conclusion

BC’s forests are a national treasure, and they need to be treated as such. Laws intended to protect forests and/or ensure that British Columbia gets value from its forests cannot remain on paper, but must be enforced. The government’s practice of shifting inspections from BC’s largest forest companies to other types of forest operations may have been effective in detecting more violations per inspection, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it is effective in protecting the environment or BC’s economic interests in our forests.

Notes: The data discussed above comes from the Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations. The Ministry of Environment’s Conservation Officer Service has, since 2006, reported on its forestry-related enforcement efforts, but does not provide comparable data regarding numbers of inspections or which category of operation the offender belongs to. However, all or virtually all of the COS enforcement actions were against individuals, rather than companies, suggesting that the levels of enforcement against “other” and “recreational” users may be even higher than the above discussion and data indicates.

We acknowledge that the above analysis is only possible because the BC Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations does report compliance and enforcement figures, and we commend them on this transparency (although we do note that for the past three years the reports have stopped reporting on the identity of forestry offenders). Staff from the BC Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations were invited to comment on a draft of this post, but we did not received a reply by the time it was published. If we receive a reply, we will post it as an update.