Fish across Canada breathed a sigh of relief when they saw the top recommendation from the Parliamentary Committee on Fisheries and Oceans’ report reviewing the Fisheries Act: to reinstate strong habitat protection for fish.

Specifically, the Committee recommended restoring legal protection against “HADD” – which stands for “harmful alteration or disruption, or the destruction, of fish habitat.” This recommendation would reverse the 2012 amendments to the Fisheries Act, which replaced HADD with the hotly contested, and vague, concept of “serious harm” to fish. Fish are happy that the Committee listened to scientists, provinces, fishing groups and conservation organizations like us about restoring their safety net.

There are 32 recommendations in the majority report from the Committee’s Liberal MPs. Both Opposition parties released dissenting opinions, also worth reading. We echo the sentiments of the NDP, who noted that the restoration of HADD could have happened a lot earlier given the widespread and vehement opposition to this change.

What else made the fish happy?

- A direction to Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) to take an ecosystem approach to protection and restoration of fish habitats so that the entire food web is preserved for fish. (Recommendation #2)

- Advocating to refine the previous definition of HADD (Recommendation #3) and include a clear definition of what constitutes fish habitat. (Recommendation #11) Fish are particularly keen to see the critical concept of environmental flow protection codified into the law as we recommended in the briefs we submitted to the Committee: Scaling Up the Fisheries Act and Habitat 2.0

- An emphasis on protecting fish habitat from key activities that can damage habitat, such as destructive fishing practices and cumulative effects of multiple activities. (Recommendation # 7)

- A move away from the fox guarding the henhouse: any changes to habitat protection in the Fisheries Act must be supported by a reduced reliance on project proponent self-assessment. Mounting evidence shows that public accountability suffers and environmental damage can occur when there is a lack of effective governmental oversight of self-assessment programs – as the BC Ombudsperson found in a review of the provincial Riparian Areas Regulation in 2014.

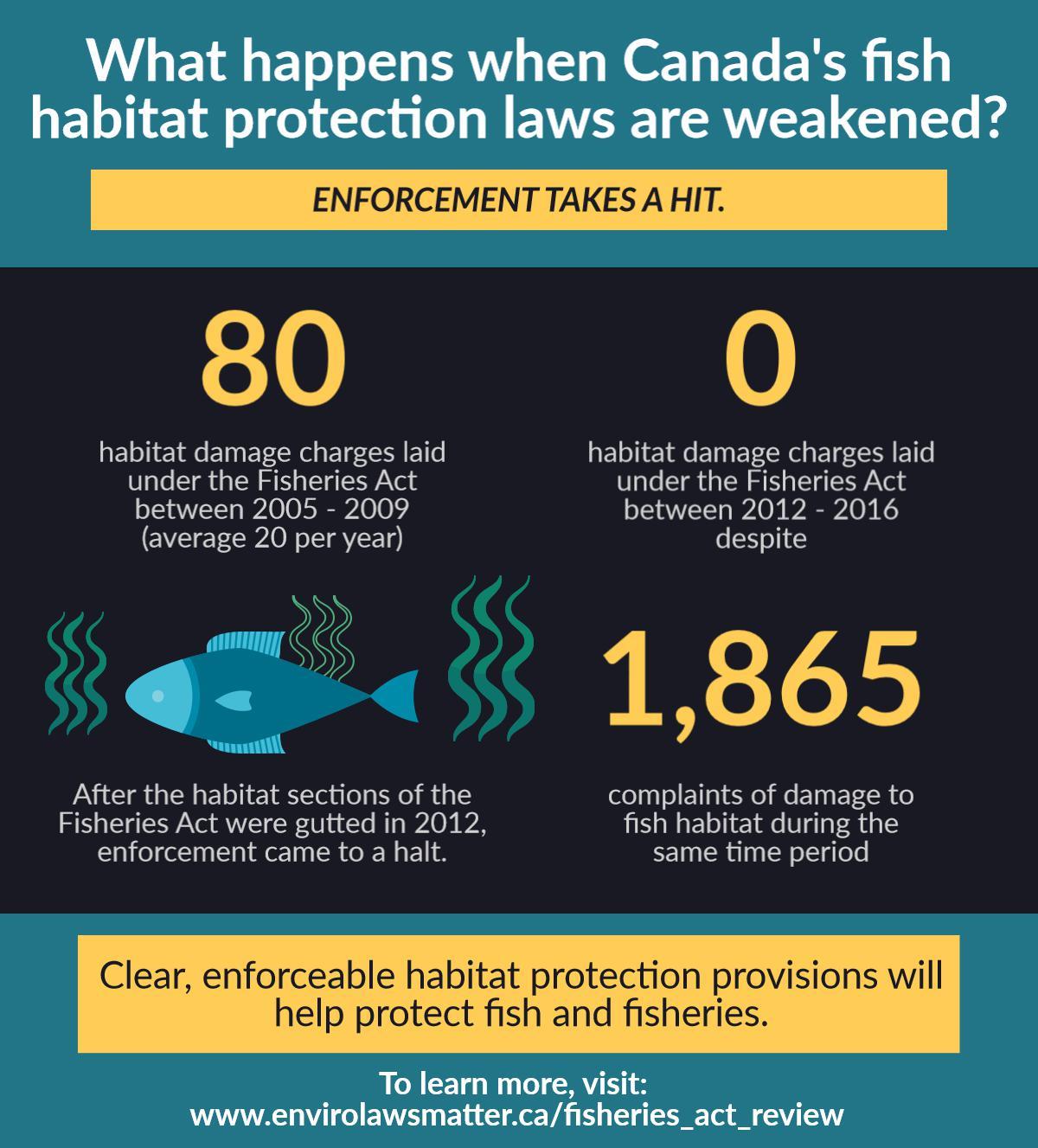

- A renewed emphasis on enforcement to counter the troubling downward trend, with zero prosecutions for fish habitat damage recorded since the Fisheries Act amendments came into effect in 2013. Recommendations to strengthen enforcement (#21-25) are essential to rebuilding a DFO field presence, as many witnesses – including top provincial officials – testified on the practically invisible DFO field enforcement efforts in recent years.

The Parliamentary Committee’s report reflects what they heard from witnesses about the first part of the Fisheries and Oceans Minister’s mandate: “restoring lost protections.”

The report also wades into the second part of the mandate, “introducing modern safeguards”; however, this part is not as thorough, with a few exceptions.

A majority of MPs on the Committee are from Atlantic Canada, and are well attuned to the need to prevent future fish catastrophes like the Grand Banks cod collapse in Newfoundland, leading to Recommendation #30, that “any revision to the Fisheries Act should include direction for restoration and recovery of fish habitat and stocks.” Fish agree.

Among the most important ‘modernization’ recommendations is to create a new public registry for fisheries decisions, projects and a host of other information, which would not only improve transparency but more importantly allow for better tracking of cumulative impacts (Recommendation #20). As reported in iPolitics, this could be one of most powerful changes in a new Act, say experts like law professor Martin Olszynski and biologist Brett Favaro.

Other key ‘modern’ legal changes suggested in the report include limiting Ministerial discretion, and guiding the exercise of that discretion more carefully.

Recommendation #15 proposes that Fisheries and Oceans Canada should create a widely representative advisory committee to provide ongoing recommendation regarding the administration and enforcement of the Fisheries Act. The Species at Risk Advisory Committee (SARAC) is a good model, and is currently being reinstated after its abrupt cancellation in 2014. Multi-stakeholder committees like SARAC – and perhaps a new fisheries-focused equivalent – improve public dialogue and understanding, and can lead to better regulation and environmental management.

Finally, fish are happy with the proposed return to “No Net Loss” and “Net Gain” habitat policies found in Recommendation #32. Clear and unambiguous policy requirements are needed for this crucial goal. Fish know they’re in danger in freshwater and marine habitats around the world, and Canada is no exception.

What don’t the fish like?

The recommendation on restoring Fisheries Act decisions as triggers for environmental assessment is not as strong as it could be. The Committee calls for the triggers to be “re-examined” rather than “reinstated.” No recommendations were forthcoming on aquaculture, despite testimony from witnesses and the potential harm arising from aquaculture regulations adopted under the amended Act’s provisions, despite the government’s pledge to implement the recommendations of the Cohen Commission (which examined the impact of aquaculture on salmon stocks).

Controversies with this industry continue on both coasts. Just last week a bio diesel spill occurred at a salmon aquaculture site in Echo Bay, BC, potentially affecting clam beaches relied on by First Nations. And the Atlantic Salmon Federation recently appealed a decision by the Newfoundland and Labrador government to exempt a planned salmon hatchery from further environmental assessment.

The report lacks depth in its treatment of Indigenous fisheries and fisheries management, which is disappointing given all the submissions and testimony that Nations provided. Reaction to the report from First Nations has been muted so far, with some exceptions. Consultations between the federal government and First Nations about the Act are ongoing.

Next steps?

Despite some concerns, the Committee’s report is well received by Canada’s fish populations – who recognize that they, and their homes, benefit from a strong Fisheries Act. Conservation groups, fishers, scientists and others who want healthy fish and aquatic ecosystems are also pleased.

The Committee’s report was tabled in Parliament on February 24th, and the government now has 120 days to respond. The fish will keep watching.

By Linda Nowlan, Staff Counsel