A shocking story from Mark Hume in the Globe and Mail on June 12th reported on a BC Government study on widespread non-compliance with the BC Water Act:

On two dozen lakes selected from around the province, researchers found 420 private property Water Act permits had been issued – but more than 4,000 waterfront “modifications” had been done. That means more than 3,500 lakeshore projects were apparently built without authorization. … This isn’t just a case of widespread non-compliance – it’s an epidemic.

The study, the Lakeshore Development Compliance Project – Defining the Issue Across BC 2008/09 – Phase I, was completed in April 2010, but has only now become public. Apparently it was introduced as evidence at the Cohen Commission.

Under the Water Act, any changes “in and about a stream” (including a lake) will require government approval. Failure to get such permission is an offence, and can result in tickets being issued or charges being laid. So the report found what appear to be 3,500 violations of the Water Act in 24 lakes.

The report emphasizes that it can’t state with certainty that all of these properties are in non-compliance, since:

- From 2000-2005 the government allowed some docks to proceed without Water Act authorizations (with Land Act licences only), but apparently did not cross reference these;

- The records of approvals from before 1995 are not available electronically and are apparently stored off-site, and were therefore not searched.

However, 65% of the observed “modifications” were below the high water mark, where, according to the report, “authorizations would typically be granted only under rare circumstances.”

BC’s Enforcement Track Record

West Coast Environmental Law has been complaining for some time that the government is failing to enforce environmental laws.

2009 did indeed have the third lowest level of enforcement (including both tickets and conviction) since 1990 – only slightly better than the second worst year (2005). More importantly, 2009 was, again as predicted, the lowest year since 1990 for convictions.

We are often asked “but what does a decrease in the number of tickets mean on the ground?” Last year, then Environment Minister Barry Penner insisted that decreasing numbers of tickets meant that more people were following the law, and therefore was a good thing. For the record, his Ministry had finished the Lakeshore Development Compliance Project study at that point, so he really should have known that problems had only recently been identified.

So this study gives a snap-shot of the impact of lax enforcement on compliance with respect to at least one law.

That being said, we can’t really criticize the current government for a drop in enforcement under the Water Act, because it turns out that the BC government has always been pathetic at enforcing the Water Act.

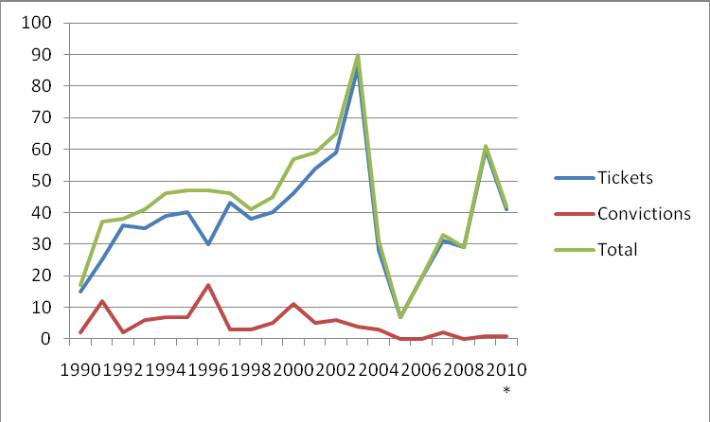

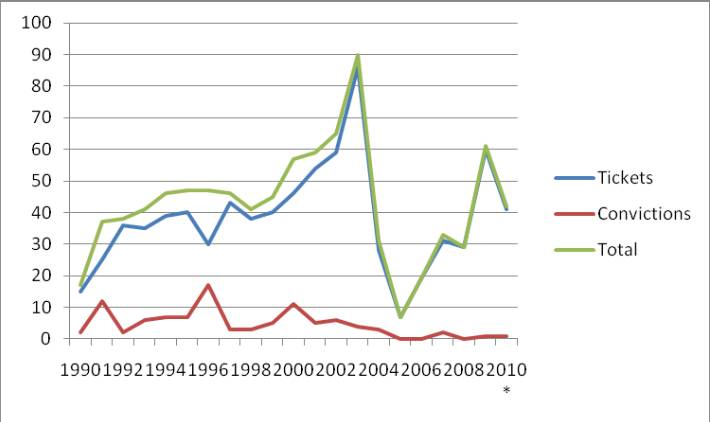

We’ve previously analyzed data for the enforcement of 6 major environmental laws, including the Water Act. That data shows that there’s been a major drop in tickets and (especially) convictions under those 6 statutes. But very few of those tickets and convictions are actually under the Water Act, and if you break out those tickets and convictions, you get a different picture. The following graph shows the total tickets and convictions under the Water Act since 1990. (Note that the data for 2010 has not been fully released, and the graph indicates our current best guess as to the 2010 enforcement levels.)

It turns out that the largest number of convictions under the Water Act in a single year (since 1990) was only 17 (in 1996), and the largest number of tickets was only 86 (in 2003). The total number of convictions over the past 20 years was 95. Plus, keep in mind that these are all of the convictions under the Water Act, not all of which would relate to illegal modification of a shore-line.

There has been a shift away from charging people under the Water Act, but given that the number of convictions was so low to begin with, this is only a modest shift. The fact is that the level of enforcement action is negligible compared to the huge numbers of apparent violations documented in the report.

Let the punishment fit the crime

I’ve written recently about the light penalties for environmental crimes. Well, let’s consider the appropriate penalty for someone who illegally alters the shore-line of their property to expand their beach, reduce erosion or otherwise increase the market value of their property.

The benefit to a property owner of these actions may be in the tens, or hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The odds of being caught seem to be staggeringly low.

The penalty? The government seems to have 3 main options that actually have teeth (i.e. not counting letting the offender off with a warning):

- They can charge an offender. If you’re convicted, it could be serious – up to $200,000 in fines and 6 months in jail (although, as we’ve seen, jail penalties are exceptionally rare in environmental cases). In 2007, Anadarko Canada Corporation and Norcana Resource Services (1999) Ltd. had to pay $65,000 and $48,000 respectively after being convicted of making changes to a stream in the course of road building. However, there have been only 4 convictions under the Water Act (subject to the final data from 2010) in the past 5 years.

- They can issue a ticket. Offenders are far more likely to get a ticket, then to be charged (about 8:1 historically, or 46:1 over the past 5 years). And a ticket carries with it a fine of (drum roll, please) $230. Wow. Now there’s a deterrent.

- The government can order the offender to restore the situation. This seems to be a tool of choice for serious offenders who are caught. Over the past 5 years there have been about 50 orders under the Water Act, perhaps half of which relate to restoring modified streams and lakes (we don’t currently have the data for this type of order going back to 1990, and they have not been included in the table above).

Next steps

As the name of the report implies, there is a Phase II on the horizon. According to the report:

Phase 2 will focus on developing, testing, and implementing tools to assist staff and partner agencies to develop strategies to address the reasons behind non-compliance over the long-term.

May we suggest that Phase 2 examine the discrepancy between the number of violations found in the report, and the small numbers of enforcement actions taken over the years. And, of course, the miniscule fines associated with ticketing.

Making the Law Work: Environmental Compliance and Sustainable Development, a publication of the International Network for Environmental Compliance and Enforcement, suggests that an effective environmental compliance regime must result in:

- A high probability of detecting violations;

- Serious implications from detection;

- Public disclosure of environmental performance;

- An enforcement framework which involves a number of different groups; and

- Effective indicators to see if enforcement and compliance methods and processes are working to ensure accountability.

We develop these concepts further in a BC context in our 2007 publication, No Response, on environmental enforcement. But it seems reasonably clear that the first two of these criteria have been entirely missing from the compliance regime around BC’s Water Act for some time.